Blog Archives

JenResources 5/11/25

Drought: While it’s sometimes difficult to write a column each week, the record of information on my blog through the years has been of help to me. I was thinking about this spring…how the rye and pastures weren’t growing, and now how the rye and wheat went to head in non-irrigated ground weeks earlier than normal. Why are they heading so early this year? I think it’s because we’ve had such warm soil temperatures coupled with low surface and subsoil moisture in non-irrigated fields. I think the plants are stressed and went into reproductive mode.

I’m concerned that pastures will also be short and head out early too. It’s good to be prepared in the event that livestock producers need additional forage. In mid-April, a Drought Preparation Webinar was held and the recording can be found here: https://go.unl.edu/2025_drought_prep_webinar. There’s also a recent CropWatch article by Aaron Berger, Livestock Educator, sharing the economic tradeoffs of grazing wheat vs. taking it for grain for those with non-irrigated acres that are drought stressed or dealing with virus diseases. You can find the full article here: https://go.unl.edu/mrny.

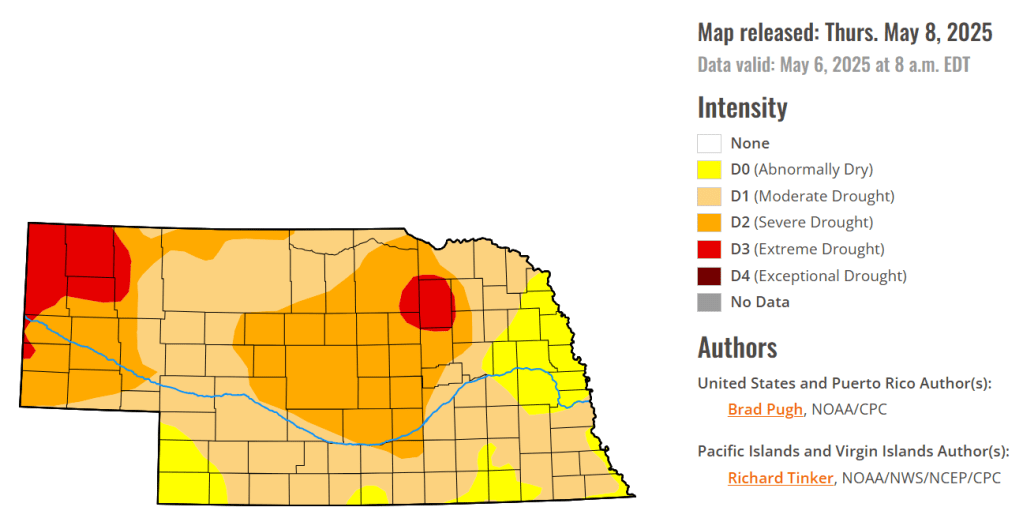

I know irrigating crops like what is occurring is reminiscent of 2023 in watering crops up and activating herbicide. No one wants the irrigation season to start this early. For curiosity, I pulled the Drought Monitor maps from this week in 2023, 2024, and 2025. 2023 is the year I think of most closely to 2025 so far, even though the drought monitor map in 2023 was much more severe than what 2025 shows. For a planting season, 2025 reminds me more of 2012 with how early everything went into the ground with a warm growing season and no cold snaps. The drought monitor map for the area of the state I serve is similar to 2024, but we also know that mid- to late-May rains changed conditions from dry to too wet in areas north and east of here. Curious as to what year(s) any of you would compare this year to?

Ultimately, we’re not in control of the weather. For the livestock producers in particular, it may be wise to have a forage plan in place in the event that forage resources run short for your operation.

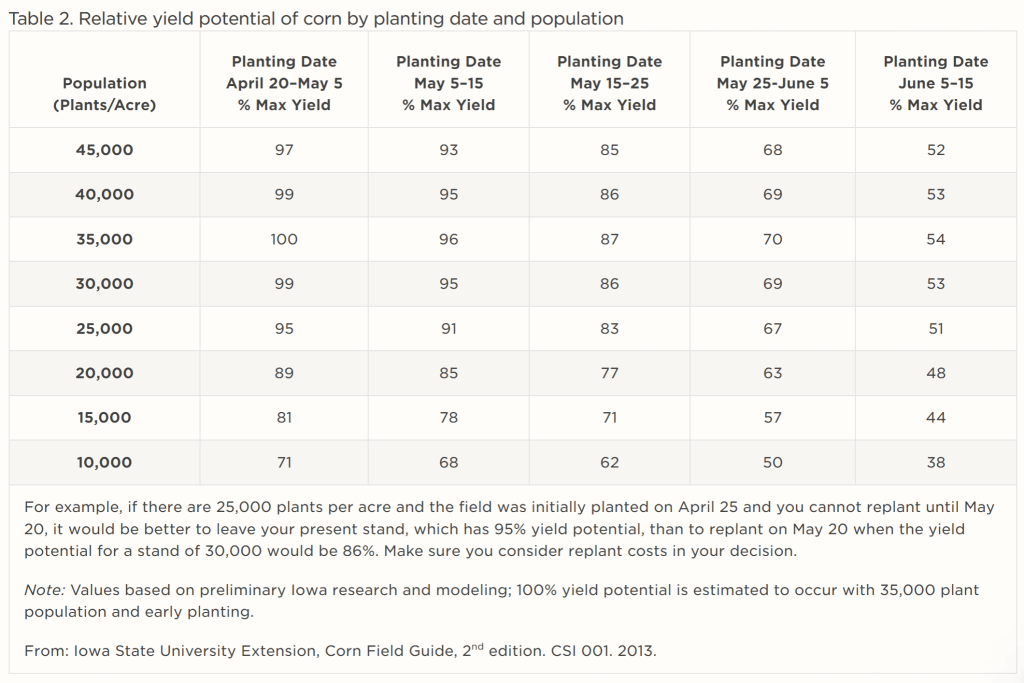

Seed Swap: On a lighter note, we have some interesting on-farm research projects this year! One we’re calling a Seed Swap. This will be my 10th year with the York Co. Corn Grower plot. Any extra seed that we vacuum out of planter boxes is mixed together and planted out. While it’s not a part of the official plot, that area has always beaten the highest yielding number in the plot by 5-10 bu/ac. And, it may not always work this way, but a handful of others also commented they’ve seen something similar. One farmer who had hosted the plot in the past had the idea of trying this via on-farm research. A group of farmers also liked the idea and they all decided on a “seed swap” where they each contributed a hybrid to be mixed together. The mix is compared to each farmer’s hybrid(s) of choice. So in 2025, we’ll have non-GMO and GMO seed swap studies. There’s also a grower who wanted to try this with soybeans, so he has a study combining different maturity groups.

A 2009 study in Ohio compared 5 hybrids vs. mixes of the hybrids. “No significant difference was seen when comparing the yield of a mixed hybrid stand to the average of the two hybrids that were used in the mixed planting. However, there was an observed tendency for the mixed hybrid treatments to out yield their single hybrid counterparts by an average of 4.2 bushel per acre.”

I realize the concept perhaps goes against what many are trying to do with increasing uniformity in fields. My hypothesis in what we’ve seen in the corn grower plot is that the range of maturities (110-120 days) allowed to catch any stragglers for pollination, there was increased diversity in disease/insect packages in combination with more defensive and racehorse hybrids. For those interested in soil health, I also think there’s something to diversity of root structures resulting in more sharing of nutrients and different microbial associations with roots. Those are just hypotheses and we’ll share what we see for results next winter!

JenREES 5/14/23

Dry Conditions: Grateful with those in the State who received rain last week! And, continuing to pray that we all might receive rain. It will come again in time. I’ve had a lot of conversations about drought with people this year. Many think back to 2012 as the great drought year, which it was that summer-winter. But actually, I don’t remember a year where in taking soil samples I’m not seeing subsoil moisture past 15-20” deep, even in irrigated fields. That may not be the case in every field, but it’s what I’ve been finding commonly this spring in this area of the State. It’s concerning.

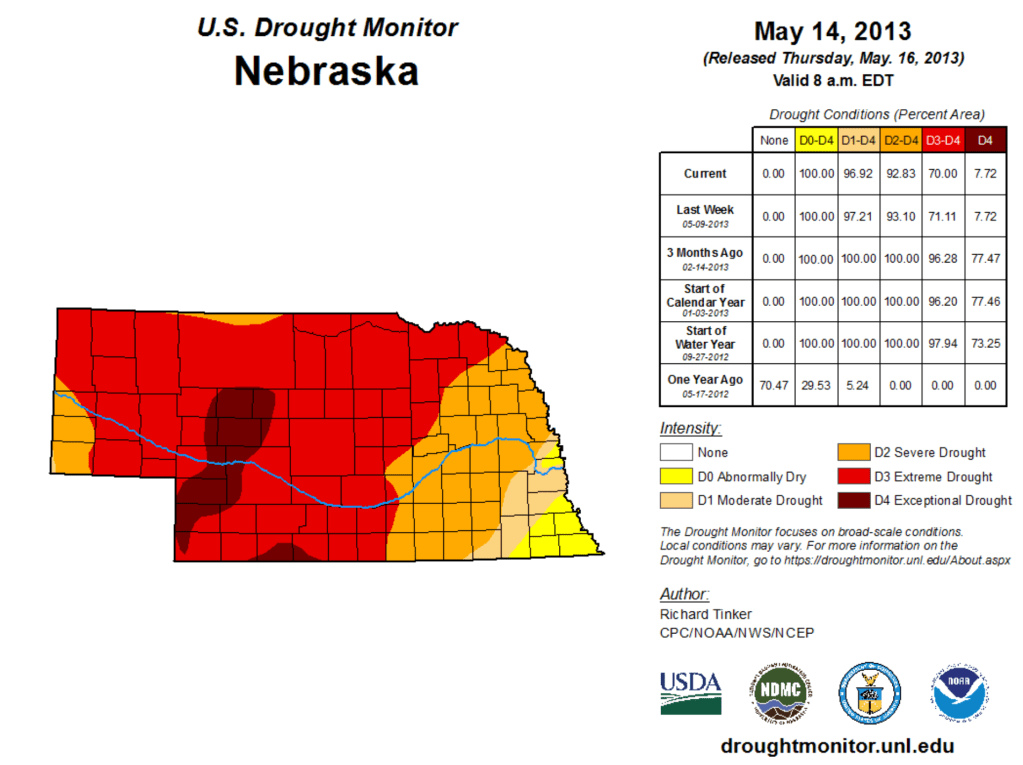

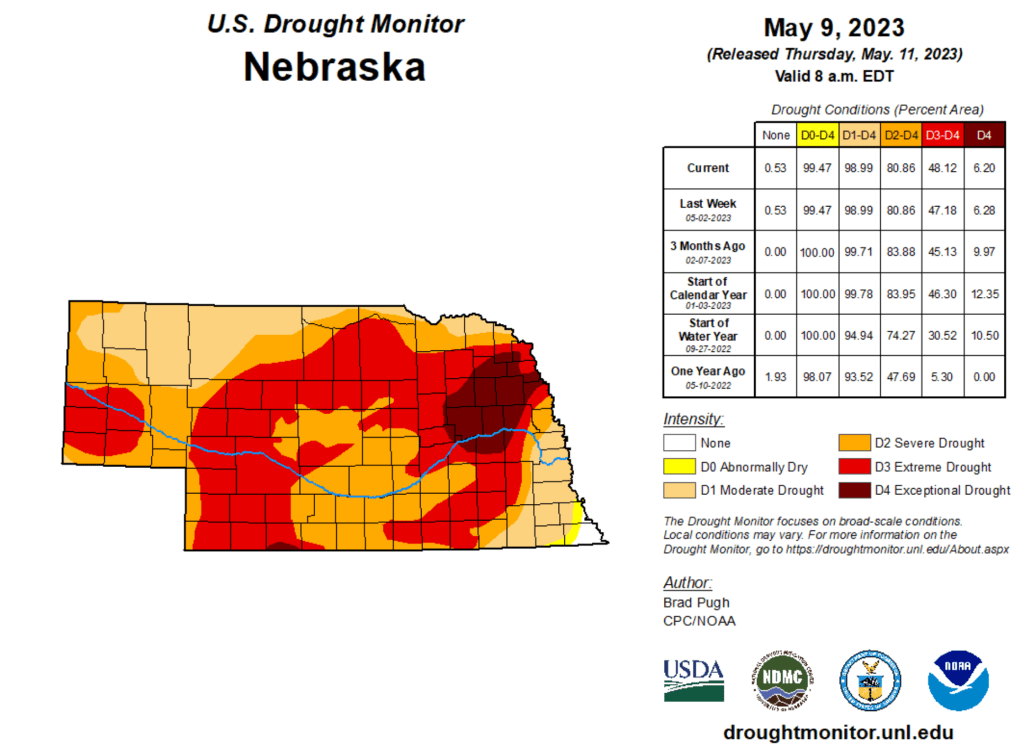

We went into 2012 with subsoil moisture in this part of the State, and I remember the dry surface conditions led to good planting weather and the spring-flowering plants were early. The Spring of 2013 lacked a full soil profile compared to the Spring of 2012 (similar to Spring 2023 to 2022). To visualize this, I pulled up images from the Drought Monitor. The May 15, 2012 map showed only 5.2% of the State was in D1-D4 drought (and technically, nothing was over D1, which is considered ‘moderate drought’). In contrast, one year later, the May 14, 2013 map showed 96.9% of the State was in D1-D4 drought. I also pulled up the May 9, 2023 drought monitor map. It shows 98.99%…so essentially 99% of the State is in D1-D4 drought. The 2013 map technically shows the drought was worse this time of year for the majority of the State, particularly western NE. 2023 shows the eastern part of NE suffering more than it did in 2013.

Ammonia Burn: The dry conditions are leading to some ammonia burn to corn seedlings. Cold and dry conditions, both of which we’ve had this year, can lead to the ammonia burning the radicle (first root emerging from the corn seed), other roots (leading to a ‘stubby root’ appearance), in addition to sometimes causing damage to the coleoptile (first true leaf). Emerged plants can look stunted and wilted in appearance. We were anticipating this could be a problem this year, particularly if at least 2″ of precipitation (we may have needed more than that) wasn’t received from time of application to seed germination.

Ammonia impacts up to a 4” radius in the soil from where it was injected; it can expand beyond this into a more vertical or horizontal oval shape depending on soil texture, moisture, and how well the band sealed. Thus, in a dry year like this, ammonia placed at 4” deep and below the seed zone can impact seedling germination and emergence. Ammonia placed deeper (6-8″) often doesn’t impact seedling germination and emergence unless there wasn’t a good seal or soil conditions change allowing ammonia to move back up the knife track. For example, if the soil dries after application allowing the knife track to open as it dries, ammonia can move towards the soil surface allowing for seedling injury in spite of the deeper application. One can also see ammonia burn later (V2-V5) from ammonia placed deeper if the conditions remain dry as roots hit the application zone and the ammonia hasn’t converted to nitrate. As much as it stinks, for those experiencing ammonia burn in fields, the only thing we can recommend is to irrigate and evaluate plant stands. For non-irrigated situations, some talked about applying anhydrous at an angle or to the side of the corn row to help reduce the number of plants that may experience ammonia burn, so hopefully that has helped.

John Sawyer from Iowa State University cited an Illinois study that shared the concentration of ammonia, “The highest concentration of ammonia is at/near the point of injection, with a tapering of the concentration toward the outer edge of the retention zone. Usually the greatest ammonia concentration is within the first inch or two of the injection point, with the overall retention zone being up to 3-4 inches in radius (as an example, with 120 lb N/acre applied early April at Urbana IL, the ammonium-N concentration in mid-May was at approximately 700 ppm at 0-1 inch, 300 ppm at 1-2 inch, and 25 ppm at 2-3 inch from the injection point).”

Evergreen Trees and bushes: Evergreen trees (especially white pine, arborvitae, junipers) and bushes (like boxwoods, Japanese Yew) continued to respire (lose moisture) all winter. May-June is the time we start seeing browning due to winter desiccation. While they look bad, wait to prune out brown/dead material till at least late May-June. As I showed a homeowner this week, a number of buds may still be developing on these brown stems and it’s best to see what will recover first.

Livestock Custom Rates: Many use the crop custom rates from UNL that are published every two years. The Ag Econ group is putting together a Livestock Custom Rates. If you’re willing to help them with this, please go to this link: cap.unl.edu/customrates/livestock.