Monthly Archives: October 2023

November 2023 Upcoming Events

Mending the Stress Fence are free webinars held on Nov. 1 and again on Nov. 29 at 12:15 p.m. It is important that we all learn how to manage our stress levels and reduce the effects of unwanted stress. Business owners, managers, farmers, and ranchers are no exception to experiencing stress. In fact, stress seems to be prevalent in rural communities at times. Too much stress can make us more accident-prone, and it can affect our overall health. This program provides information on identifying common stressors, recognizing stress symptoms, and managing stress. Register: https://ruralwellness.unl.edu/stressfence.

Bodily Fluid Clean Up Training Webinar will be held Nov. 1 from 2-4 p.m. The training is designed for employees in businesses, schools, child care facilities responsible for properly cleaning up bodily fluids, but anyone interested can attend. Certificates provided. Registration: https://go.unl.edu/ewat.

Cover Crop Grazing Conference will be held Tuesday, November 7th at the Eastern Nebraska Research Extension and Education Center near Mead. Registration and trade show are from 8:30-9:30 a.m. with program beginning at 9:30 a.m. Dr. Bart Lardner from the University of Saskatchewan will kick off the program sharing on annual forage production and grazing strategies and Dr. Mary Drewnoski will share more on this topic later in the day. The program also features a producer panel, field tours, and lunch and breaks. For more info. and to register, please visit: https://go.unl.edu/ys5b.

2023 Transition to Organic Farming Conference: Are you thinking about transitioning to organic farming or are a newly certified organic farmer? This one-day conference put together by a team of UNL researchers, extension personnel, and local farmers will have sessions on how to improve soil fertility, manage weeds, and develop resilient crop rotations for organic grain farms. Panel discussions with organic producers will be part of the program. Come, learn, and mingle with other growers, vendors, educators, and researchers. This event is held Wednesday, November 8th from 9:00 a.m.-3:30 p.m. (8:30 a.m. registration) at the Eastern Nebraska Research and Extension Center near Mead. There’s no charge. More info. and registration at: https://go.unl.edu/myu0.

So You’ve Inherited a Farm…Now What? will cover Nebraska land industry topics for farms and ranches. Those include evaluating current trends in land values and cash rents, strategies for successful land transitions, lease provisions, legal considerations and managing communication and expectations among family members. Creating and adjusting estate plans will also be covered. The program is free to attend, and lunch or refreshments will be provided at each location. Pre-registration is requested by one day prior to each workshop. Programs in this area of the State include:

- November 30th from 1-4 p.m. at Cornerstone Bank (529 Lincoln Ave.) in York (Register at 402-362-5508).

- December 13th from 10:30 a.m.-2 p.m. at the Extension Office in Beatrice (402-223-1384)

- Jan. 24th from 1-4 p.m. at the Extension Office in Hastings (402-461-7209)

- Feb. 6th from 10:30 a.m.-2 p.m. at the Extension Office in Lincoln (402-441-7180)

- Feb. 21 from 1-4 p.m. at the Extension Office in Central City (308-946-3843)

Tax Strategies for MidWestern Farm and Ranch Women: An upcoming virtual workshop series for Midwestern farm and ranch women will teach the basics of tax planning for agricultural operations. Men who are interested may also attend. Hosted by women in agriculture extension programs at UNL, K-State and Purdue University, the three-part series will be held from 6:30 to 8 p.m. Central time on Tuesday, Nov. 28, Dec. 5 and Dec. 12. A comprehensive range of tax topics relevant to agricultural producers in Nebraska, Kansas and Indiana will be covered, including an introduction to income taxes, completing Schedule F forms, claiming deductions, tax strategies to shift income and lower tax bills, and compliance requirements. More info. and registration at: https://wia.unl.edu/taxes.

Farmers and Ranchers College: Dr. Kohl is returning to the Opera House in Bruning on Dec. 7th at 1 p.m. The title of his presentation is “Economic Shockwaves: Challenges and Opportunities”. You can RSVP at 402-759-3712.

System’s Approach to Soybean White Mold

Grateful for seasons, for fall, and that we have such beautiful fall colors this year! For whatever reason, it just doesn’t seem like we’ve seen colors like this for a few years and several have commented about the beauty this year. May we take time to notice the beauty around us each day! Also grateful for harvest being completed or nearing completion for many! Each day is one day closer to the end!

White Mold in Soybean: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (the pathogen that causes white mold) impacts over 400 plant species from 75 families including soybean, dry bean, potato, sunflower, peas. Host weed species include: pigweeds, velvetleaf, henbit, lambsquarters, ragweeds, nightshades, mustards, sunflower. Cover crop hosts include: peas, lentils, turnips, radishes, collards, common vetch, (alfalfa and clover to a lesser extent). Just reading all that is discouraging. The fungus survives in a hard, black structure called a sclerotia that looks like mouse/rat droppings and can survive in the soil for 5 years (3 years in no-till fields). Frequent irrigation, plant wetness/fog/cool conditions at flowering (like we had in 2023), narrow rows, high plant populations, and cooler weather conditions of 46-75F allow the sclerotia to develop apothecia (look like circular tan mushrooms). Under a specific pressure, the apothecia shoot spores into the canopy where they infect the soybean plants whenever they land on senescing soybean flowers.

Flowering occurs from R1-R5 in indeterminant soybeans. Thus, why white mold is difficult to control and why we can see it develop so late into the year. The fungal infection moves from the flower into the stem, disrupting water transport. Thus, why you will often see plants that look wilted as an early symptom even before you see the signs of the white fungal growth. Wilting of plants leads to premature death impacting yields like we saw with large yield hits this past year. New sclerotia are formed within and also stick out of the plant stem and pods. They fall to the ground and the cycle continues when a susceptible host is grown.

So, what do we do about it? The following information is for fields that have a history of white mold. I’d suggest looking at this from a system’s approach. One piece is to consider varieties with disease resistance. I won’t argue that’s important. However, I’m honestly hesitant to start there as I’m unsure we have strong disease packages. And some defensive varieties give up too much yield. This is my perspective and I don’t expect people to agree. For now, I suggest finding the strongest yielding genetics first because there’s large yield variation in soybean.

From there, it becomes managing the other factors that can aid in disease. Manage weeds and avoid susceptible cover crops in the field. Crop rotation is not effective if it’s only a 2 year corn/soy rotation. While I realize they won’t work for everyone’s operation and they take more management, using small grains like cereal rye before soybeans is a tool that can help with both weed and disease suppression and doing so adds another crop to a 2 year rotation. Avoid irrigation at flowering (I realize 2023 was tough) and seek to irrigate deeper and less frequent.

There’s also tradeoffs within the system regarding row spacing for weed or disease control. Results from 18 site-years of research from Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Iowa showed:

- If planting in row spacings of 15 inches or less and in fields with a history of white mold, use a seeding rate no greater than 110,000 seeds/ac.

- If planting in fields with a history of severe white mold, widen the row spacing to 30 inches and use a seeding rate no greater than 110,000 seeds/ac. UNL research shows you don’t give up yield with final plant stands at 100,000 plants/ac.

- Fungicide applications remain an effective tool for reducing white mold levels if applied between the R1 (most effective) and R3 (less effective) growth stages. Fungicides provide 0-60% control. They’re most effective if sprayed below the canopy.

- Not all fungicide products are equally effective at controlling white mold, with Endura® remaining the most effective product if applied between the correct growth stages.

- Consider downloading the Sporecaster app for white mold to better time fungicide apps based on weather conditions (found to be 81.8% accurate).

Most biological control agents should be applied at least 3 months before flowering for fungal colonization. Biological control agents and seed treatments such as Heads Up® were shown as effective tools to reduce severity of white mold and SDS based on Iowa State research. Plant nutrition is also showing promise and that’s something I’d like to try next year with a few growers; please let me know if you’re interested. Hydrogen peroxide products had little to no success in Wisconsin research (provided only 4 hours of activity killing spores). None of the things mentioned here are exclusive, but a combination of many of these factors as a system’s approach can help in the battle against white mold.

To view tables of the fungicide research results for white mold go to: https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/publications/modern-integrated-management-practices-for-controlling-white-mold-of-soybean

Soybean Seed Size and Yield Impacts

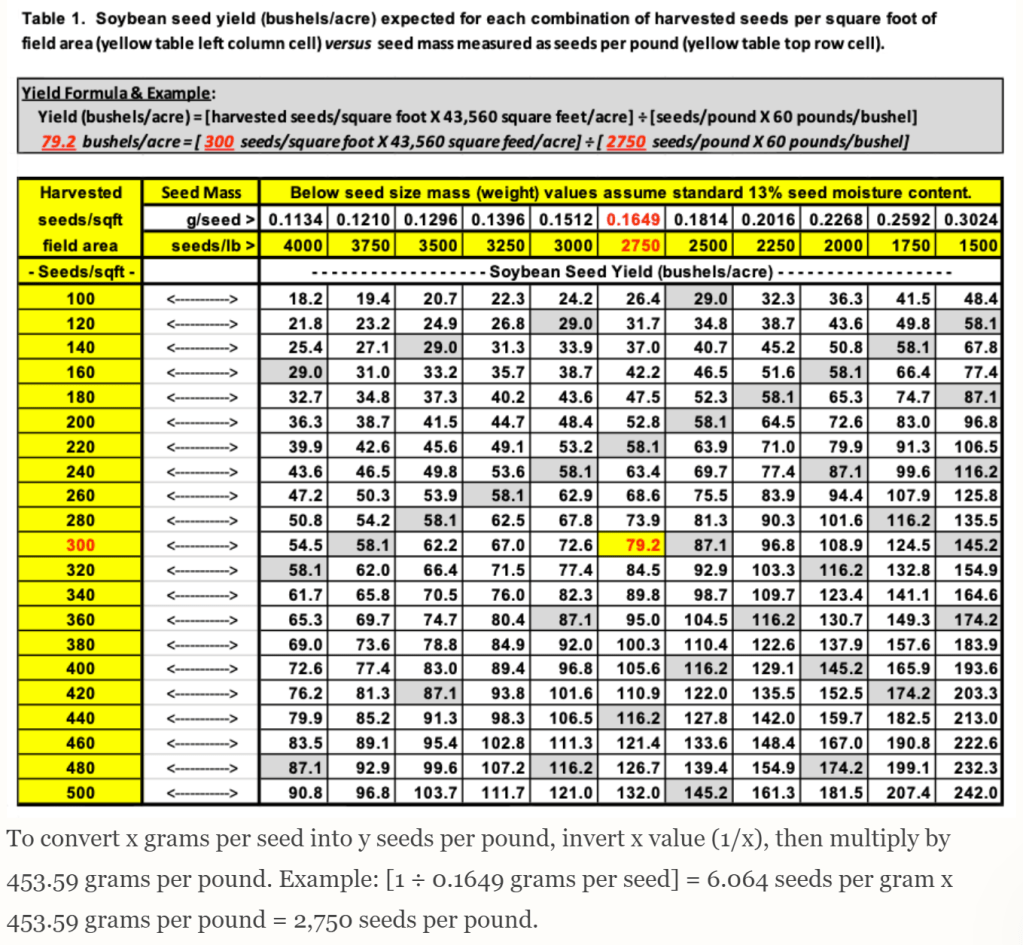

Soybean Seed Size and Yield: Dr. Jim Specht, Emeritus UNL Soybean Physiologist, wrote a couple articles for CropWatch (https://cropwatch.unl.edu). One contains a quick method to determine yields using seed size just prior to harvest. The other is about water stress timing. Sharing key points that applied to soybean yields in our area of the State this year when it came to weather, soy development, seed size, and yield. This doesn’t reflect disease impacts.

During soybean reproductive development, three stages — R1-R2 (flowering), R3-R4 (podding), and R5-R6 (seed-filling) — occur successively during July and August in the growing season. Soybean yield is ultimately a function of two components: the harvested seed number (in terms of unit land area), and the seed mass (weight of the average harvested seed). Seed number is set during the R1 to R4 stages of flowering and podding, though abortion of pods or seeds in those pods can occur in the later R stages. Seed mass (i.e., size) is set during the R5 to R6 stages of seed-filling, as the seeds undergo enlargement until the R6 stage ends at the onset of the R7 (physiological maturity) stage.

Jim and colleagues conducted a 3-year study in the 1980’s looking at the drought-stress sensitivity of seed number and seed size during different R stages. It involved 14 Group 0-Group 4 soybean varieties using seven treatments — each consisting of a single irrigation application, but each treatment differed with respect to the R stage coinciding with the single irrigation event.

When the single irrigation was applied during flowering, they saw a substantial increase in seed number, yet also a lower seed mass compared to the control rainfed treatment. This indicated that when water stress is mitigated during flowering (but not thereafter), soybean plants will set more seeds, but also end up making those seeds smaller when water is not adequate thereafter. We normally don’t recommend irrigation during flowering to avoid disease onset, but this year was a year where irrigation was necessary in many fields in this part of the State.

In contrast, when a single irrigation is applied during seed-fill (R5-R6), fewer seeds are set (and/or retained) due to prior water stress, but the mass of those fewer seeds is optimized due to the late-applied single irrigations that mitigate any coincident water stress.

They also found a response pattern coinciding with an irrigation event occurring at R3.5 and R4.5 (podding) that showed plants in that stage are conditioned to enhance seed mass while still increasing seed number to some degree. Irrigating at this stage resulted in the highest yields among treatments. Thus, why we typically encourage first irrigation of soybeans at R3 in our silt-loam soils. Additional research in the early 2000’s verified this.

However, it wasn’t reality for us to start irrigating at R3 this year. Many were irrigating since planting or as early as V2 with gravity irrigation after ridging tiny beans. The research also showed a full-season multiple irrigation treatment that resulted in maximized seed number, but seed mass was not increased beyond the increase achieved with single irrigation at R3.5. Thus, by irrigating all season (or in a season where rainfall provides no water stress), seed number (which is set before seed mass) is prioritized by stress-free plants relative to optimization. As we think about this past year, many fields may have experienced moisture stress at some point and all experienced heat and other environmental stresses.

Many soybeans that were early planted and early maturing experienced the stress of a hot and dry late June as flowers began setting which transitioned into a mostly wet/cool July during the seed number setting stages of R1-R2 (flowering) and R3-R4 (podding). The transition to a dry/hot August during the seed mass setting stages of R5-R7 (seed-filling) resulted in a reduction in the size of the harvested seeds, which means that more (small) seed will be required per pound. Thus, impacting yield. In comparison, the later maturing beans (including early planted ones), were in those flowering and podding stages longer to take advantage of the cooler conditions. They were also in the seed fill stages into mid-September during a period of cooler temperatures. Thus, I’ve heard better yield and seed size with Group 2.8-Group 3.1 beans.

While the weather is outside our control, I hope this is helpful in thinking through this past year. For risk mitigation going forward, I think it shows the importance of planting varying maturity groups to help spread risk with variations in weather conditions each year.

Prussic acid test strips: I ordered a roll of these, so if you’re grazing sorghum species, it’s a quick way to determine the presence of prussic acid, especially with light frost events. Otherwise, we recommend to pull cattle for at least 5 days post-freeze. They’re in York Ext. Office right now, so please call if you want to pick some up.

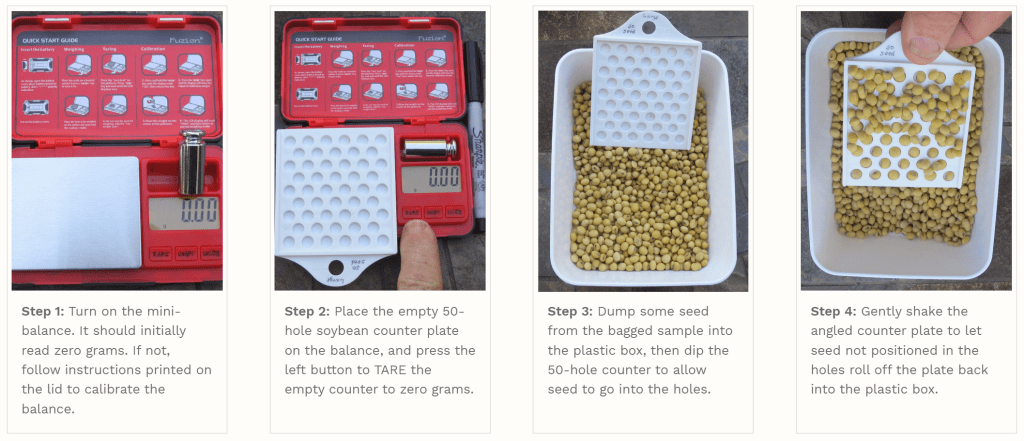

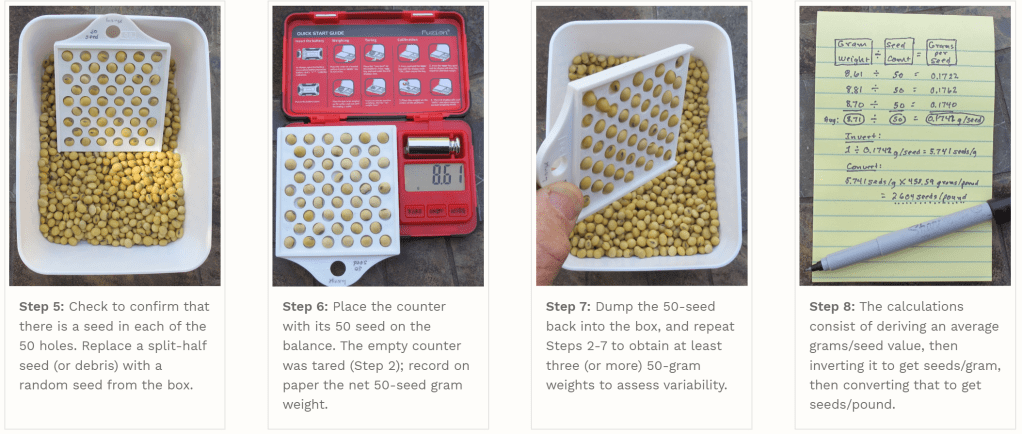

The following is how Dr. Jim Specht walks through determining soy yields just prior to harvest using seed size. These photos are via Dr. Specht.

Looking at the above chart, Alex Harrell from Georgia who reported a record soybean yield of 206.8 bushels/acre in 2023 suggested that the harvested seed in field likely had a seed mass of around 1,675 seeds/pound. Thus, a large seed size with (doing the math) around 477 seeds per square foot on a plant population of 77,000 plants/ac.

JenREES 10/8/23

Soybean Cyst Nematode: 2023 was a year for soybean diseases. I’ve been thinking about the soybean disease problems we’ve had and am planning a series of columns to talk through thoughts on management. Will focus on soybean cyst nematode for this week.

After soybean harvest is a prime time to sample for soybean cyst nematode as they’ll be at their highest levels in the soil. Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) is considered the #1 soybean disease in the U.S. as it can rob yield (up to 40%) with or without the presence of symptoms on soybean plants. When symptoms are present, they can include patchy areas of fields that may contain chlorotic and/or stunted plants. Digging up plants and carefully looking around the roots, one may observe tiny white specks that look like sand grains. With closer observation, if it is SCN, the specks will appear lemon-shaped as the female soybean cyst nematode. Technically, when the female body turns brown and dies is when it is called a ‘cyst’. Each cyst protects and contains up to 400 eggs each. When soybean is planted, juvenile nematodes hatch from eggs within the cysts during the right moisture and temperature conditions. The nematodes migrate to soybean roots where they infect, feed, breed, and then females produce new cysts full of eggs. This lifecycle occurs 3-4 times during the summer, thus, SCN populations can rapidly increase in a field in one year.

I saw that this year, a handful of times. Most field situations didn’t only have SCN as the problem, but I saw SCN populations rapidly increase from the first time fields were sampled to the next time. As you or agronomists are taking soil fertility samples this fall, split part of the 0-8” (or 0-6”) sample for testing for SCN. Or, take the soil sample in areas where the yield monitor showed yields were very low, patches where you saw disease, or field entryways. It’s also wise to take a sample from a good portion of the field for comparison. In soybean fields, take the sample a few inches off the old soybean row. However, SCN samples can also be taken from corn or other crop fields to help inform decisions if rotating to soybean next year. Place the sample cores (12-20 in total) in a plastic bucket, mix, then place in your sampling bag. I use quart-sized ziplock type bags, but there’s also SCN sampling bags available at local Extension Offices or directly from the UNL Plant and Pest Diagnostic clinic (402-472-2559). Label the bag with your contact info., field name, and that you want SCN analysis. Also be sure to fill out a completed sample submission form requesting SCN analysis and mail the samples to the UNL Plant & Pest Diagnostic Clinic (1875 North 38th Street, 448 Plant Science Hall, Lincoln, NE 68583-0722). There’s no charge for the sample analysis thanks to the Nebraska Soybean Board and your checkoff dollars. Knowing if you have SCN is the first step in management. Will share more on management in future columns.

Caring for Drought-stressed trees/shrubs: With the continuing dry conditions, this is a critical time to prepare woody plants for winter and prevent winter injury, especially to evergreens. Dry fall conditions can reduce the number of leaves, blooms and fruits trees produce the next season. Trees often delay the appearance of drought-stress-sometimes months or years after the stress occurs. Drought-stressed trees are more susceptible to secondary attack by insect pests and disease problems, such as borers and canker diseases, which can cause tree death. When watering, moisten the soil around trees and shrubs, up to just beyond the dripline (outside edge of tree leaf/needle canopy), to a depth of 8 to 12”. Avoid overwatering; but continue to water until the ground freezes as long as dry conditions persist. Use a screwdriver pushed into the soil to gauge the depth of watering.

Cedar beetles (Cicada parasite beetles): Have gotten a few calls about numerous beetles on ash and other trees that were crawling on them and flying around. The ones I’ve received samples of are cedar beetles, also known as cicada parasite beetles, which were new for me to learn about. They are about one inch long, and dark brown or black. The males have short, comb-like antennae. The beetles are harmless to trees and are laying eggs in the bark cracks. Larvae hatch, travel down tree cracks and burrow through soil looking for cicada nymphs to feed on their blood. So, they’re considered a parasite of cicadas, not of trees, and no control is needed.

Cedar beetles/Cicada parasite beetles

JenREES 10-1-23

Harvest Update: It’s been a fairly full month of harvest! I’ve heard much disappointment in yields thus far. Perspective for me comes from helping serve eight counties this past year and seeing such a range of conditions. Have struggled to find ways to encourage as I talk with growers. I’m just so grateful harvest is here as, to me, every field finished is one field closer to being done with 2023! I also realize that’s not a great way to look at a year, but it’s honestly where I’m at. Thus far, non-irrigated soybeans have averaged 20-25 bu/ac in much of the northern counties I serve and 4-10 bu/ac in the southern tier of counties. Pockets receiving a little more rain got above 30 bu/ac. Irrigated soybeans are mostly going 65-75 bu/ac, which I realize is a huge disappointment. Last week I shared the high heat the third week of August coupled with disease and soybean gall midge were all factors. Hearing 45-50 bu/ac for those with higher levels of disease (SDS and white mold). Early season beans were extra impacted by the high heat with small beans like “bbs’s”. Later maturing beans being harvested now were at an earlier development stage during the high heat and seem to be coming out better in size and yields.

Non-irrigated corn is all over the board depending on rainfall, hail damage, and practices involved. Have seen everything from no/few ears present and not even combined to nearly 120 bu/ac where there were more rains on no-till ground. Heard an exceptional non-irrigated yield for this year of 145 bu/ac on no-till corn on milo ground with more rain in July. With higher ET, I think there’s potential for some powerful irrigated corn in spots, but it also depends on ability to maintain enough water, impact of the smoke on solar radiation, development stage during that 3rd week of August and how quick the fill period went from dent to black layer. GDDs from 2012, 2022, and 2023 were fairly similar in pattern (based on data from York). June 2023 varied from nearly the same to 50 GDD more than June 2012. July 4 is when things changed with 2012 accumulating more GDD until the 3rd week of August of 2023. From then on, 2023 and 2012 have showed essentially the same GDD accumulation until this past weekend (Sept. 30) when 2023 is around 37 GDD higher than 2012. GDDs in 2023 follow a highly similar pattern to 2022 other than the June time-frame and Aug. 22-Sept. 17 being higher in 2023. This CropWatch article (https://go.unl.edu/kefo) was suggesting near average to below average yields for irrigated corn in our area of the State due to the high heat period from Aug. 22-Sept. 12, 2023. During that time, the weather data at Clay Center showed higher solar radiation, ET, min and max temp compared to the 30 year average. We’ll see what happens and wishing you safety during harvest!

Frost and Prussic Acid: It’s not predicted for frost yet but in case temps drop to freezing this coming Friday, be aware of the potential for prussic acid poisoning for cattle out on sorghum species (sudangrass, sorghum sudan, sorghum/milo). UNL beef researchers were experimenting with prussic acid test strips (cyantesmo test paper) this past year when grazing annual forages; they can be a quick indicator of the presence of prussic acid or not. University of Kentucky shares a protocol for use: https://forages.ca.uky.edu/files/cyanide_quick_field_test_using_cyantesmo_paper_updated_2019.pdf. Essentially, collect the plant material the animal would graze (small tillers have most potential for prussic acid). Cut the material into smaller pieces and place into a gallon sized ziplock bag with a 1” piece of the test strip paper. Seal and leave the bag in the sun/warm place for 10 min. The paper will turn blue at the presence of cyanide or remain white if it’s not present. It doesn’t provide a level but is a quick way to know if there’s risk of prussic acid poisoning or not. One roll of test paper goes a long way and is a little pricey, but could be used amongst several producers in an area for a quick test. Just something to consider as there’s a lot of forages planted in the area this year. For those who planted pearl millet, prussic acid is not a concern.

Minute Pirate Bugs: One thing I appreciated in the midst of drought was the reduced number of mosquitoes, chiggars, and ticks (at least that bothered me anyway). Fall is such a beautiful time of year to be outside until the tiny biting black/white minute pirate bugs (insidious flower bugs) appear as they have now! They’re actually a beneficial predator of thrips, mites, aphids, tiny caterpillars, and insect eggs in crop, garden, landscapes, and wooded areas in the summer. This time of year on warm, sunny days, they bite humans they land on. One doesn’t need to worry about them injecting a venom, feeding on blood or transmitting disease. People’s reactions to the bites range from no reaction to swelling like a mosquito bite. Unfortunately, there’s also no method of controlling them. Insect repellents don’t work as they aren’t attracted to carbon dioxide like mosquitoes are. They are attracted to light colored clothing, so wearing darker colors and long sleeves can help when being outdoors during warm, sunny days. Otherwise, work outdoors on cool, cloudy days.