Blog Archives

Soybean Seed Size and Yield Impacts

Soybean Seed Size and Yield: Dr. Jim Specht, Emeritus UNL Soybean Physiologist, wrote a couple articles for CropWatch (https://cropwatch.unl.edu). One contains a quick method to determine yields using seed size just prior to harvest. The other is about water stress timing. Sharing key points that applied to soybean yields in our area of the State this year when it came to weather, soy development, seed size, and yield. This doesn’t reflect disease impacts.

During soybean reproductive development, three stages — R1-R2 (flowering), R3-R4 (podding), and R5-R6 (seed-filling) — occur successively during July and August in the growing season. Soybean yield is ultimately a function of two components: the harvested seed number (in terms of unit land area), and the seed mass (weight of the average harvested seed). Seed number is set during the R1 to R4 stages of flowering and podding, though abortion of pods or seeds in those pods can occur in the later R stages. Seed mass (i.e., size) is set during the R5 to R6 stages of seed-filling, as the seeds undergo enlargement until the R6 stage ends at the onset of the R7 (physiological maturity) stage.

Jim and colleagues conducted a 3-year study in the 1980’s looking at the drought-stress sensitivity of seed number and seed size during different R stages. It involved 14 Group 0-Group 4 soybean varieties using seven treatments — each consisting of a single irrigation application, but each treatment differed with respect to the R stage coinciding with the single irrigation event.

When the single irrigation was applied during flowering, they saw a substantial increase in seed number, yet also a lower seed mass compared to the control rainfed treatment. This indicated that when water stress is mitigated during flowering (but not thereafter), soybean plants will set more seeds, but also end up making those seeds smaller when water is not adequate thereafter. We normally don’t recommend irrigation during flowering to avoid disease onset, but this year was a year where irrigation was necessary in many fields in this part of the State.

In contrast, when a single irrigation is applied during seed-fill (R5-R6), fewer seeds are set (and/or retained) due to prior water stress, but the mass of those fewer seeds is optimized due to the late-applied single irrigations that mitigate any coincident water stress.

They also found a response pattern coinciding with an irrigation event occurring at R3.5 and R4.5 (podding) that showed plants in that stage are conditioned to enhance seed mass while still increasing seed number to some degree. Irrigating at this stage resulted in the highest yields among treatments. Thus, why we typically encourage first irrigation of soybeans at R3 in our silt-loam soils. Additional research in the early 2000’s verified this.

However, it wasn’t reality for us to start irrigating at R3 this year. Many were irrigating since planting or as early as V2 with gravity irrigation after ridging tiny beans. The research also showed a full-season multiple irrigation treatment that resulted in maximized seed number, but seed mass was not increased beyond the increase achieved with single irrigation at R3.5. Thus, by irrigating all season (or in a season where rainfall provides no water stress), seed number (which is set before seed mass) is prioritized by stress-free plants relative to optimization. As we think about this past year, many fields may have experienced moisture stress at some point and all experienced heat and other environmental stresses.

Many soybeans that were early planted and early maturing experienced the stress of a hot and dry late June as flowers began setting which transitioned into a mostly wet/cool July during the seed number setting stages of R1-R2 (flowering) and R3-R4 (podding). The transition to a dry/hot August during the seed mass setting stages of R5-R7 (seed-filling) resulted in a reduction in the size of the harvested seeds, which means that more (small) seed will be required per pound. Thus, impacting yield. In comparison, the later maturing beans (including early planted ones), were in those flowering and podding stages longer to take advantage of the cooler conditions. They were also in the seed fill stages into mid-September during a period of cooler temperatures. Thus, I’ve heard better yield and seed size with Group 2.8-Group 3.1 beans.

While the weather is outside our control, I hope this is helpful in thinking through this past year. For risk mitigation going forward, I think it shows the importance of planting varying maturity groups to help spread risk with variations in weather conditions each year.

Prussic acid test strips: I ordered a roll of these, so if you’re grazing sorghum species, it’s a quick way to determine the presence of prussic acid, especially with light frost events. Otherwise, we recommend to pull cattle for at least 5 days post-freeze. They’re in York Ext. Office right now, so please call if you want to pick some up.

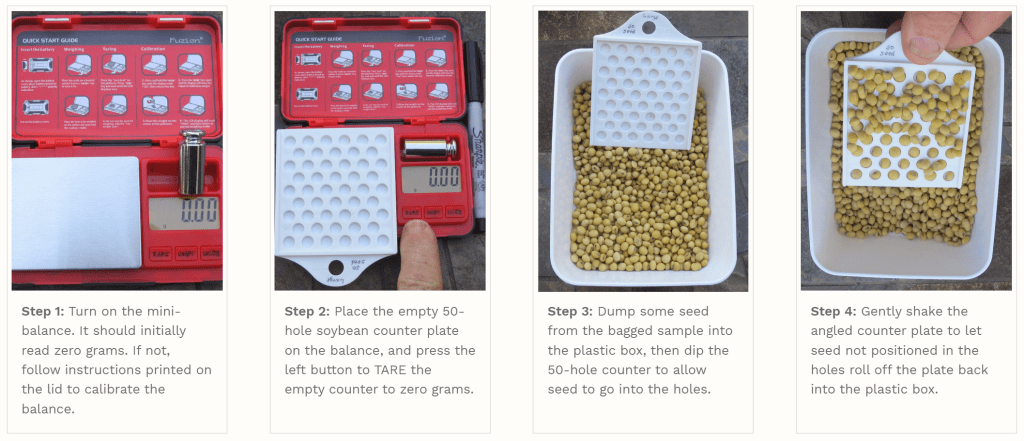

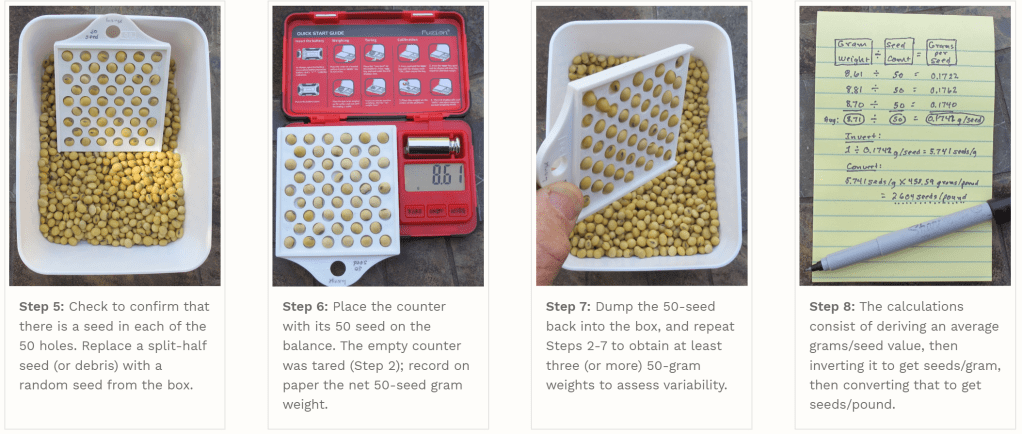

The following is how Dr. Jim Specht walks through determining soy yields just prior to harvest using seed size. These photos are via Dr. Specht.

Looking at the above chart, Alex Harrell from Georgia who reported a record soybean yield of 206.8 bushels/acre in 2023 suggested that the harvested seed in field likely had a seed mass of around 1,675 seeds/pound. Thus, a large seed size with (doing the math) around 477 seeds per square foot on a plant population of 77,000 plants/ac.