Blog Archives

Soybean Seed Size-Yield Impacts

Soybean Seed Size and Yield: It’s been awhile since we’ve seen full pods throughout plants (instead of flat pods with shrunken seed) and I’ve also noticed more 4-bean pods on upper nodes of plants this year. It has been deceiving in that soybeans with greener stems and some leaves were right at that point of being ready to harvest in the 13-14.5% range. Now I’m hearing a lot of dry beans are coming out again.

For the most part, soybeans have been of good seed size and quality. There are areas where “bb’s” are being observed again. I’ve heard reports of this from producers in the non-irrigated portions of southern Seward county and Saline counties. In those situations, plants often held onto leaves and just died due to lack of moisture; however, the seed number is still allowing for decent yields. This made me think of information I shared last year from Dr. Jim Specht, Emeritus UNL Soybean Physiologist, so resharing.

During soybean reproductive development, three stages — R1-R2 (flowering), R3-R4 (podding), and R5-R6 (seed-filling) — occur successively during July and August in the growing season. Soybean yield is ultimately a function of two components: the harvested seed number (in terms of unit land area), and the seed mass (weight of the average harvested seed). Seed number is set during the R1 to R4 stages of flowering and podding, though abortion of pods or seeds in those pods can occur in the later R stages. Seed mass (i.e., size) is set during the R5 to R6 stages of seed-filling, as the seeds undergo enlargement until the R6 stage ends at the onset of the R7 (physiological maturity) stage.

Jim and colleagues conducted a 3-year study in the 1980’s looking at the drought-stress sensitivity of seed number and seed size during different R stages. It involved 14 Group 0-Group 4 soybean varieties using seven treatments — each consisting of a single irrigation application, but each treatment differed with respect to the R stage coinciding with the single irrigation event.

When the single irrigation was applied during flowering, they saw a substantial increase in seed number, yet also a lower seed mass compared to the control rainfed treatment. This indicated that when water stress is mitigated during flowering (but not thereafter), soybean plants will set more seeds, but also end up making those seeds smaller when water is not adequate thereafter. We normally don’t recommend irrigation during flowering to avoid disease onset. This year we had some rains with cloudy conditions during a portion of the flowering period. However, rains shut off for the most part after that. I think that’s why we’re seeing the smaller seed size with lots of beans in some of the extremely dry areas.

In contrast, when a single irrigation is applied during seed-fill (R5-R6), fewer seeds are set (and/or retained) due to prior water stress, but the mass of those fewer seeds is optimized due to the late-applied single irrigations that mitigate any coincident water stress.

They also found a response pattern coinciding with an irrigation event occurring at R3.5 and R4.5 (podding) that showed plants in that stage are conditioned to enhance seed mass while still increasing seed number to some degree. Irrigating at this stage resulted in the highest yields among treatments. Thus, why we typically encourage first irrigation of soybeans at R3 in our silt-loam soils. Additional research in the early 2000’s verified this.

The research also showed a full-season multiple irrigation treatment that resulted in maximized seed number, but seed mass was not increased beyond the increase achieved with single irrigation at R3.5. Thus, by irrigating all season (or in a season where rainfall provides no water stress), seed number (which is set before seed mass) is prioritized by stress-free plants relative to optimization. While the weather is outside our control, I hope this is helpful in thinking through this past year. For risk mitigation going forward, I think it shows the importance of planting varying maturity groups to help spread risk with variations in weather conditions each year.

The full articles can be found at UNL CropWatch: One contains a quick method to determine yields using seed size just prior to harvest. The other is about water stress timing.

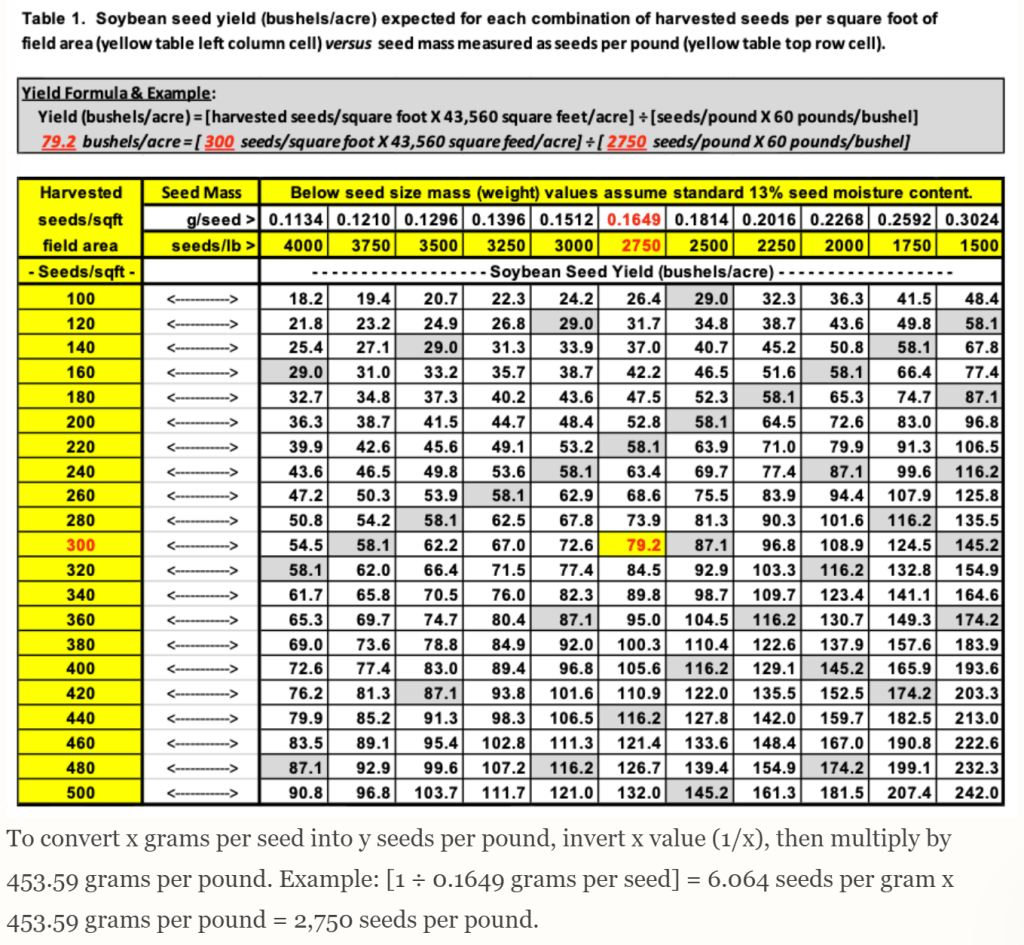

For Alex Harrell from Georgia with the record breaking yield of 218 bu/ac in 2024, he mentioned aiming for large seed size. Based on this chart, assuming around 450 seeds per square foot, he’d be achieving around a 1500 seeds/pound seed size.

In 2023, Alex Harrell reported a record soybean yield of 206.8 bushels/acre in 2023, and he suggested that the harvested seed in field likely had a seed mass of around 1,675 seeds/pound. Thus, a large seed size with (doing the math) around 477 seeds per square foot on a plant population of 77,000 plants/ac.

JenREES 9/24/23

It was so great to hear rain/thunder and to receive some rain Thursday night! I don’t know how many felt this too, but it was so hard to want to work Friday after harvest has been going so hard. I saw that rain as such a gift for rest; hopefully you were able to take a little time that day for some rest too or intentionally choose that the next time we receive rain!

Old World Bluestem: Last fall, a producer near Garland shared there was a grass he had noticed his cattle weren’t eating and it was spreading in his native pasture. It was confirmed by the UNL Herbarium to be Old World Bluestem. I was grateful he gave me a tour of his pastures and it appeared that Roundup was killing it. Received another call in the Garland area this year. This resource from K-State shows ID characteristics and management info: https://www.frontierdistrict.k-state.edu/livestock/docs/2%20Old%20World%20BluestemsID.pdf. It is very drought tolerant, so it may be more visible now in the midst of drought. It’s actually not in the same genus as our native bluestems and has more characteristics of silver bluestem as they’re both in the Bothriochloa genus. It doesn’t green up as early as our native big bluestem but it will produce a seedhead quicker. It has a yellowish appearance to the leaves and stems. While cattle can graze it early, they often avoid it once it produces a seedhead. It’s extremely competitive and replaces native plants and forbs. Would encourage you to scout native pastures for any grass clumps that cattle don’t seem to be eating. If you see Old World Bluestem, make note of its location. I can also help ID the plant if needed. Management includes 2 lb/ac Glyphosate at the 4 leaf stage and again before seedheads are produced. Because it can contain both rhizomes and stolons, one may need to treat a good 1-3 feet beyond the clump. It also produces a prolific seed bank where it may take a few years of treatment on newly emerging plants before the seedbank is exhausted. When purchasing native grass seed for pastures, check with seed suppliers that the seed is free of old world bluestem. Another source of contamination can be from feeding hay, particularly from Texas and Oklahoma. It’s become an increasing problem in Kansas as well.

Soybean Yields: Last week received numerous calls and texts from people disappointed with soybean yields. That high heat period in August was really the last straw for non-irrigated soybeans, but it also greatly impacted irrigated soybeans. Other specific factors this year for the irrigated soybeans have included all the disease from irrigating since planting (white mold, sudden death syndrome, phytophthora, Fusarium root rot). Soybean gall midge has also been a factor in some fields, particularly in Seward County.

Small Grain Cover Crops: While there’s been some tremendous challenges with cover crops this year with moisture use in the midst of drought, they are a management tool for helping with disease and weed challenges. For example, a producer in the Gresham area who grew cereal rye for the purposes of weed control did see good weed control in those fields overall in spite of other challenges he faced. At least one of those fields was prone to white mold. I’d seen this in the past, but the rye kept the fungus from getting up into the soybean canopy and infecting the soybean plants. That’s in spite of how much extra he had to irrigate in the beginning of the season to get his beans up with a tall rye cover crop. Some have applied two fungicides for white mold this year and were still battling it. There’s tradeoffs to everything.

I’m often asked if I’m ‘sold out’ on cover crops. I don’t recommend cover crops to everyone because it takes another level of management. However, if a person is looking for a different tool for pest problems and is willing to look at management in another way, cover crops have the potential to help. So, if you’re dealing with soybean diseases like sudden death syndrome and/or soybean cyst nematode, small grains, particularly oats, have been proven via research to help reduce the fungus and nematodes. And, oats winterkill so they’re an option I was sharing with people who didn’t want to worry about a small grain surviving next spring. It’s late to plant oats right now, but they can be an option to consider for next spring or fall. Rye is another option before soybean because of the biomass it produces for weed control against palmer, its help in reducing soybean diseases, and it can be planted throughout the winter. I’ve been recommending wheat before corn and seed corn because it doesn’t get as much biomass and there’s not the same scare factor to plant green into it because of that. All these small grains will take moisture, but we’ve also seen them recycle moisture and nutrients back into the system in the July time-frame for May-terminated plants (research shows 6 weeks post-termination). While not a silver bullet, small grains are an option to help with pest problems if you’re open to managing a field differently. Feel free to contact me if you’d like to talk more about this.

JenREES 9-27-20

Bean harvest was rolling this week. Hearing non-irrigated beans in the area ranging from 40-60 bu/ac and irrigated beans going 70-90+. Regarding solar radiation and some wondering about smoke impact on drydown, I ran data from 9/1/20 though 9/26/20 for Harvard and York weather stations. Then looked at long term average for this same September time-frame from 1996-2020. Both stations showed slightly higher solar radiation in 2020 compared to the long-term average for September (York: 379 and 372 langleys respectively) (Harvard: 383 and 376 langleys respectively). And, it was higher yet for 2020 when I queried Sept. 10-26 for same time periods. So, unsure solar radiation was the factor impacting drydown for this part of the State?

Small Grains and Weed Control: Been watching weed control particularly in soybean fields. For future columns/winter programs, I’d like to hear from you. What weed control approaches have worked in your soybean and corn fields? I’m curious about all systems and all types of weed control options. Please share at jrees2@unl.edu or give me a call at the Extension Office. Thanks!

In the past, I’ve shared weed control begins at harvest by not combining patches of weeds or endrows full of weeds. I realize that’s difficult to do, and for many fields, we’re past this point. From a system’s perspective, another option to aid weed control is to plant a small grain such as wheat, rye or triticale this fall. We had a whole edition of CropWatch devoted to wheat production here: https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2020/september-4-2020. Wheat provides an option for both grazing and grain. Rye provides the best option for earliest green-up/growth in the spring and longest seeding time as it can be seeded into December. Triticale provides the most biomass but produces the latest into late May/early June. All keep the ground covered from light interception penetrating the soil surface which allows weed seeds to germinate. While I’ve observed this in farmers’ fields, there’s also recent research from K-State that supports the impact of a small grain in rotation for weed control.

One study looked at marestail (horseweed) and palmer amaranth control from 2014-2015 in no-till soybeans at six locations in eastern Kansas. They also found the majority of marestail emerged in the fall (research from UNL showed up to 95% does). They compared five cover crop treatments including: no cover; fall-sown winter wheat; spring-sown oat; pea; and mixture of oat and pea. Cover crops were terminated in May with glyphosate and 2,4-D alone or with residual herbicides of flumioxazin + pyroxasulfone (Fierce). Ten weeks post-termination, palmer amaranth biomass was 98% less in winter wheat and 91% less in spring oat compared to no cover crop.

Another study in Manhattan from 2015-2016 compared fall-seeded rye; a residual tank-mix of glyphosate, dicamba, chlorimuron-ethyl, tribenuron-methyl, and AMS; and no fall application. Four spring treatments included no spring application or three herbicide tank mixes: glyphosate, dicamba, and AMS alone or with flumioxazin + pyroxasulfone (Fierce) as early preplant, or as split applied with 2/3 preplant and 1/3 at soybean planting. They found the fall rye completely suppressed marestail while fall herbicide suppressed biomass by 93% and density by 86% compared to no fall application. They also found rye to reduce total weed biomass (including palmer amaranth) by 97% or more across all spring applications. In both studies, soybean yields were best with the combination of cover crop + herbicides or the combination of fall + spring herbicides compared to no cover and no herbicides.

The way I think about this for conventional systems is that the use of a small grain in the system reduces the pressure on the chemicals for having to provide all the control. It also buys some time for chemical control, perhaps even removing one application (based on these studies, small grain delayed at least a month till 50% palmer germination). Economically, while there’s the expense of seeding and purchasing the small grain seed, what are the other economics to consider? What could the small grain provide by reducing an additional chemical application, adding a forage crop after harvest, selling seed (if there’s a market), selling straw (depending on location for moisture savings & ability to get a cover back in for weed control), etc.? Just some considerations this fall looking at weed control by adding a small grain.

JenREES 10-20-19

Crop Update: So grateful for this past week’s weather in aiding harvest progress! Also grateful to all the growers who worked with me in on-farm research this year and for all the studies harvested this past week!

grateful to all the growers who worked with me in on-farm research this year and for all the studies harvested this past week!

One of the more frequent questions/comments I’ve received the past few weeks is regarding yields. It sounds like irrigated yields for corn and even soybean are around 5-15% lower than what farmers hoped for in this part of the State. Most aren’t necessarily ‘bad’ yields, just not what was desired. Irrigated corn is mostly going 225-245 bu/ac with high-yielding genetics and everything else aligned correctly going 250-265 bu/ac. And, as more fields are harvested, there may be some better yields due to the long grain fill period. There’s irrigated fields of soybeans that did 50-60 bu/ac. What is positive is non-irrigated yields for both corn and soybeans with non-irrigated beans sometimes out-yielding the irrigated ones.

The impacts of the difficult cold, wet planting season could be seen season-long in fields

Plant to plant variability impacting kernels/ear.

with uneven plant emergence and eventually variable ear height and kernels/ear. That plant to plant variability can add up to yield impacts more than one realizes. There’s also field variability due to ponding/flooding in fields, hail/wind damage, and additional challenges during harvest with wind and moisture leading to lodging and/or ear loss and some soybean shatter.

The high humidity and leaf wetness along with cool, wet weather allowed for more disease in both corn and soybean. Perhaps one reason why non-irrigated corn and soybean are yielding well was due to reduced disease pressure from reduced plant population and increased air flow. I know of a handful of irrigated soybean fields in 2019 planted on seed corn acres where, to the line, the soybean on seed corn had more sudden death syndrome (SDS) pressure and less yield than the soybean on soybean corners of fields. I had never before seen this so striking.

Same soybean variety. Yellow area is soybean planted on seed corn residue under pivot with heavy SDS pressure. Green area to the line is soybean on soybean in pivot corners.

My hypotheses: 1-Test for soybean cyst nematode in the seed corn acres vs. corners. Anything that will move soil will move SCN, including equipment. 2-Fusarium virguliforme (pathogen that causes SDS), reproduces best on corn kernels followed by corn residue, followed by soybean seeds and residue. Even if the seed corn acres had a cover crop and were grazed, cattle don’t easily pick up loose kernels lost to the 2018 hail storm or harvest loss. 3-SCN in the field + great conditions for SDS in 2019 allowed for synergistic effect of more SDS and yield loss.

Cloudy weather also played a role in photosynthesis and ultimately yield. Dr. Roger Elmore and colleagues shared the following research on shading and yield impacts. “Many researchers have investigated the effects of lower solar radiation on corn using shade cloth of different densities. These can effectively block solar radiation by 10% to 90% or more (e.g., Schmidt and Colville 1967, and Reed et al. 1988). Invariably they found that shading the crop two to three weeks after silking (R1) reduced yields more than shading before R1. Most also find that hybrids differ in their responses to shading.” (This can help explain the tip back due to kernel abortion some of you asked me about after pollination). “Very few researchers used shade cloth during the grain-fill period, which would be similar to the reduced solar radiation period central Nebraska experienced the third week of August.

Early et al., 1967, shaded plants around the “reproductive phase” for 21 days as well as during the “vegetative stage” for 54 days and the “maturation phases” for 63 days. Shading during reproductive stages reduced plant yields the most, but 30% shading during the maturation stages ― what we consider the seed set and grain-fill periods (R2-R6) ― not only reduced yield per plant 25% to 30% but also reduced kernels per plant and the amount of protein per plant. Researchers in a new study shaded plants from silking to maturity (R1-R6) (Yang et al., 2019). Shading reduced yields more with higher plant populations than with lower populations.” (This may also help explain why non-irrigated fields with lower plant populations may have good yields in spite of cloudy conditions in 2019).