Category Archives: Diseases

2025 Yields

This harvest was a difficult one, plagued with breakdowns, slow-going in storm-damaged corn, and disappointing yields. While there were a few reports of decent yields, the overwhelming majority of farmers and seed dealers in the area have been disappointed. Honestly, I was worn down and needed a mental break before I could address this in writing. I asked Dr. Roger Elmore, Dr. Tom Hoegemeyer, Dr. Bob Nielsen, and Dr. Eric Hunt if my reasoning was on track and for their additional thoughts and am grateful to them.

Major Point: People are looking for solutions, but increased nitrogen rates, more fungicide applications, and tillage are not the answers. What went right? Balanced nutrient management with reduced nitrogen inputs, TIMELY fungicide application, and proper irrigation management are future keys.

We began the season with dry planting conditions. I was arguing we were potentially drier than Spring 2023 with the observations about rye and pastures not growing. Crops went into the ground quickly without cold snaps. Several farmers were completely done planting in April. Irrigation began early to get moisture into seedbeds and to activate herbicide. Plant stands and emergence were uneven, evidenced again at harvest with varying ear sizes and plants with ears that didn’t pollinate. I think that impacted us more than we realized. The Memorial Day weekend rains saved us.

A relief was that rain kept falling in spite of it varying greatly in timing and amounts. Some experienced higher non-irrigated yields in corn and soybeans compared to irrigated fields. That nearly always is due to too much irrigation and timing of those irrigations, often occurring right before a significant rain event.

We had a few wind/hailstorms in July and the fairly widespread Aug. 8-10 wind/hail event, which York Co. escaped. Much of the year we received lower than average solar radiation (which includes photosynthetically active radiation or PAR). There were several periods of cloudy/hazy/smoky days. Research utilizing shade cloth revealed 25-30% potential yield loss with shading occurring from R2-R6 stages in corn. As Dr. Roger Elmore pointed out, the hybrid maize model was predicting average yields at the end of the growing season in spite of the low PAR, which would suggest biotic (living) factors being the greater issue. Photosynthetic stress on plants can also include southern rust impacts on leaf tissue and stalk rots. I’m wondering if irrigation prior to heavy rain events exacerbated the fusarium crown rot/gibberella stalk rot we saw? Dr. Tom Hoegemeyer wondered the same thing. “Photosynthetic stress and stalk rot go together like beans and weenies. Each one can cause the other. We MAY have had some early infection with Fusarium/gib due to saturated soils/etc. As you know, high N rates, lower K available and a dozen other stress sources make it worse.”

High night-time temperatures burn sugars that should go into ears to fill kernels. I mentioned my concern about this throughout July and August. By mid to late August, ears began pre-maturely drooping, cutting off the food supply to kernels. Looking at kernels in numerous fields at harvest time, they appeared shriveled/pinched at the base. Dr.’s Tom Hoegemeyer, Roger Elmore, and Bob Nielsen all attribute that to stress occurring before black layer in which the kernels prematurely died before completing the normal black layer process. I feel the greatest contributors of this were the high night-time temperatures and the stresses of southern rust and stalk rots. Dr. Eric Hunt also mentioned the high humidity, particularly in York County due to the sheer amount of irrigation which may have led to increased disease pressure including stalk rots.

Dr. Bob Nielsen: “Your description of the kernels makes me think that kernel development was prematurely halted. Although, honestly, severe reductions in photosynthetic leaf tissue prior to BL (black layer) due to southern rust etc. or early onset of severe stalk rots would also prematurely shut down kernel development. And, of course,…(large) ears with excellent kernel set create a huge demand for photosynthate during grain fill, which exacerbates the negative effects of severe loss of photosynthetic leaf tissue and predisposes the stalk and root tissue to rapid fungal rot infection and development.”

Dr. Tom Hoegemeyer summed it up: “I think we had lots of issues that caused PS (photosynthetic) stress, some of which impacted our irrigated acres worse than our dryland acres. (My home dryland area had lots of 200 to 220 bpa corn and 65 to 70 bpa soybeans. After a dry spring, we had more rain than we’ve had for years). Irrigated corn in the area often wasn’t as good as the dryland, even with more N applied. The more stressors (hot nights, light limitations, too high N for the amt of light/PS–exacerbating disease issues, multiple leaf diseases combined with high humidity, continuous corn, etc.) the bigger the yield loss. And, in some instances, I think adding water to these fields hurt more than it helped.”

Sources:

York: -21 MJ/m2

Grand Island: -9.7 MJ/m2

Lincoln: -25.2 MJ/m2

Falls City: -28.3 MJ/m2

Norfolk: -10.7 MJ/m2

Wayne: +19.7 MJ/m2

West Point: -1.3 MJ/m2″

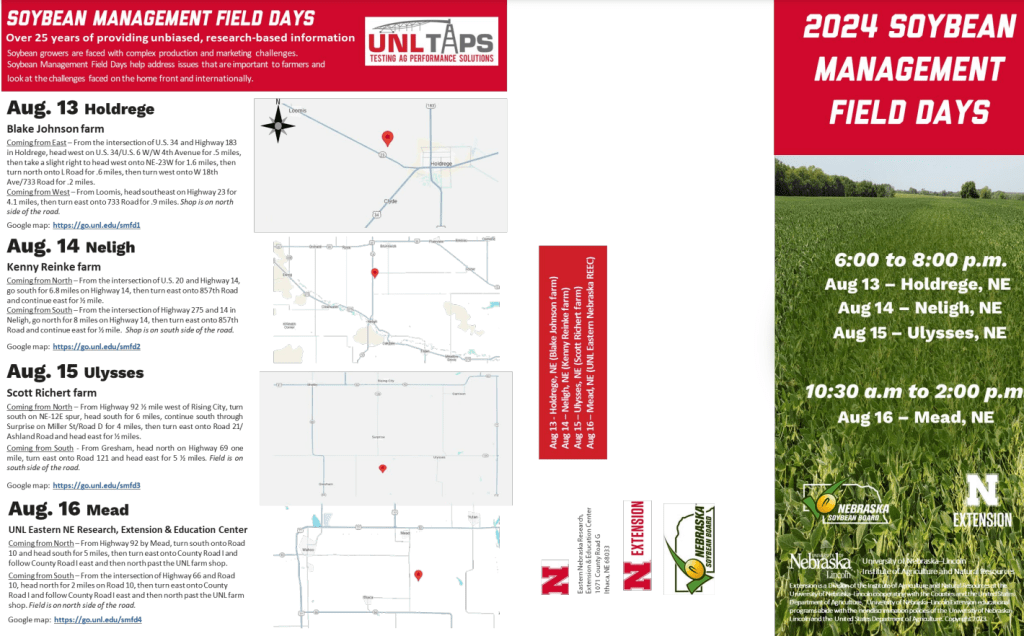

Southern Rust Myths

The following article, originally published in CropWatch (https://cropwatch.unl.edu/mythbusters-southern-rust-edition/) , was written by Dr. Tamra Jackson-Ziems and Kyle Broderick. High disease levels of southern rust were present in 2025, impacting yields. This article addresses the misinformation we are hearing about southern rust before decisions are made for next year’s growing season.

“Myth #1: Overwintering Rust: The southern rust fungus cannot overwinter in Nebraska. (It cannot survive in corn residue or soil).

The southern rust fungus (Puccinia polysora) needs to infect living, green corn in order to survive, and there is no known alternate host. Thus, the fungus can’t overwinter anywhere the climate doesn’t support corn growth through the winter months.

In fact, our rust fungi are likely blown north into the United States from subtropical locations, such as parts of Mexico, where corn is grown year-round. The southern rust fungi typically reach Nebraska in late July; however, this year they arrived earlier than usual, with the first confirmed sighting on July 9 — the earliest on record for the state.

Myth #2: Infected Grass: Southern rust doesn’t infect brome or other grasses nearby.

Rust fungi tend to have very narrow host ranges, infecting only one or a few plant species. Because several species of rust thrive under the same environmental conditions, it’s not unusual to see multiple plant species showing rust symptoms at the same time — even though they’re caused by different pathogens.

Myth #3: Super Strains: There is no new “super strain” of southern rust fungus.

… the severity we observed was due to prolonged periods of extremely favorable weather conditions — southern rust thrived under high relative humidity and average temperatures around 80°F. Southern rust…has been confirmed in 19 of the last 20 years…. If you remember 2006, you might recall another historic outbreak centered in south-central Nebraska. That season also brought delayed corn planting from spring rains, followed by ideal weather for rust development during the first two weeks of August. Many fields suffered stalk weakening and lodging, which caused memorable harvest challenges.

Myth #4: Fungicide Failures: Fungicides did not fail to control southern rust this year.

Although yield data are still coming in, most reports indicate that fungicides performed wellagainst southern rust this year. During years with substantial disease pressure, differences in fungicide performance become more apparent, underscoring the importance of selecting effective products and applying them at the right time. Results from multiple states, compiled by the Crop Protection Network, reinforce these findings. Remember: Even the best product can’t perform well without good coverage and proper timing, especially in a season like 2025 when disease pressure was unusually high.” The full article can be viewed at: https://cropwatch.unl.edu/mythbusters-southern-rust-edition/.

JenResources 7/14/25

It was a blessing to get away for the national ag agents conference and then on vacation! The keynote speaker was Dwayne Fisher who is the VP Marketing and partner at Champion Produce Sales in Idaho. His speech was about relationships. My takeaway from him was, “The more, more, more is creating less, less, less when it matters most, most, most. When we don’t feel we have time for one more thing, pause and take time to do something for someone else. (Regarding people)-Notice them, Value them, Serve them, Encourage them. We can’t replace Relationships.” This was a helpful reminder and “shot in the arm” for me; hopefully, helpful in some way for you too.

For the ag tour, I learned about wool production and marketing and toured a sheep ranch that was 45 miles from Yellowstone National Park in the mountains. The rancher shared the challenges of grazing thousands of sheep in the mountains with wolves and bears migrating from the park and killing sheep. The specific wolves and bears have to be tracked and ID verified before they can be eliminated. They work with experts to use drone technology and game cameras to help identify the specific animal. At the wool-buying stop, we learned that China dictates the market based on weekly wool sales in Australia. Australia sells more wool in one week than what the U.S. sells in 1 year. The take-home from the wool-buying stop was to buy more natural fibers like wool and cotton.

Fungicides: Received many questions last week on fungicide applications to corn and soybeans. First, tar spot is still at low levels where it’s been found in fields and hasn’t hit the 5-7% thresholds. It prefers temps in the 60’s-70’s, which to me explains why we’ve mostly seen it get worse in fields at the end of the growing season. I realize a lot of fungicide is going on corn. Economically and threshold-wise, I’d wait as long as possible before applying a fungicide. The research from Indiana showed that it was still economical to apply through milk-early dough stage. Waiting will allow for residual for when you may need it later in the season if tar spot or southern rust take off. There won’t be residual left for those making apps now. Just for consideration as the economics don’t justify multiple applications.

For soybeans, if the field had never had white mold in the past, I would not worry about a fungicide for white mold. If it’s a seed corn/soybean or corn/soy rotation field and had white mold in the past, one could aim for one fungicide application at full flower (R2). If you’ve had 2 years of corn followed by beans this year, you probably don’t need a fungicide. And, if you planted soybeans green into a small grain, again, you shouldn’t need a fungicide as we’ve seen small grains keep white mold at bay. I realize I’m more conservative with recs compared to most, but this is based on economic thresholds and understanding the pathogen and crop rotation history. Also, a reminder if you’re interested in using plant nutrition in either corn or soy for on-farm research, please let me know.

Summer Grazing Field Day July 24 will be held at Eastern NE Research & Extension Center near Mead from 9 a.m.-2 p.m. (Registration at 8:30 a.m.). The cost is $20 and they are requesting RSVP for lunch count. More info here: https://beef.unl.edu/news/summer-grazing-field-day-strategies-beat-slump/. The day will be casual and discussion-based. Take a look at the summer phase of a double-crop annual forage system—where warm-season forages like sudangrass (with or without sunnhemp) are being grazed by both cow/calf pairs and stockers. Additional topics include:

- How to manage warm-season annuals to get the most out of them

- What the performance data says (ADG, stocking rate, carrying capacity)

- How the economics compare between cow/calf and stocker systems

- New prussic-acid free sorghum-sudangrass variety

- Virtual fencing in action

Plant Nutrition and Disease

Tar spot of corn was found in several Nebraska counties. We are not recommending fungicide applications at this time due to the research from Purdue University and other states. They found it best to wait till disease severity was 5-7% and corn was from tassel to dough stage of development. More info. at: https://jenreesources.com/2025/06/17/tar-spot-of-early-corn-update/.

What to do now:

1-Scout fields and wait till a 5-7% threshold on leaves before applying fungicide

2-Observe fields as to which hybrids have more tolerance to tar spot

3-When irrigating, consider less frequent and deeper irrigations, https://go.unl.edu/vipj

4-Consider plant nutrition?

In managing pests and pathogens, few mention plant nutrition or alternative options. Healthy humans and animals are less prone to disease; why not the same with plants? A book called “Mineral Nutrition and Plant Disease” shares published research on roles of minerals in aiding or managing disease. It was written by Dr. Don Huber, Professor Emeritus of Plant Pathology from Purdue University and there’s an updated version that I have.

There’s a lot of unknowns about tar spot and its control. Dr. Huber shared that the tar spot lesions contain oxidized manganese in addition to the fungal spores. Several journal articles referenced the black “freckles” in Goss’ wilt and the vascular plugging in the systemic version also contain oxidized manganese. When manganese is oxidized, it creates a manganese deficiency in the area which doesn’t allow for photosynthesis. The area runs out of energy and can’t defend itself resulting in disease expansion. Many of us in ag understand that micronutrients are chelated in plants in the process of applying specific herbicides. Companies have developed products to help with chelation and to stimulate plants sooner from the shut-down that occurs from applying herbicides.

I’m wondering about the opportunity to use plant nutrition right now to help stimulate plant defense mechanisms? We may need fungicide at some point, but we don’t right now. I have no research on this, but to me, it makes sense. When we have early symptoms of a cold, we’re told to take zinc to stimulate our defense system. Manganese and Zinc both travel in the xylem and they aid in plant defense signaling. Addition of zinc and copper in particular can reduce manganese oxidation, aiding in plant defense responses. Thus, wondering if zinc, copper, and manganese may help with preventing and fighting tar spot? Boron and sulfur could play a role too. The addition of Calcium increases the oxidation, so it shouldn’t be used alone for this situation. Manganese, Zinc, Copper, Boron, Sulfur all aid in defending plants against pathogens.

If you’re interested in trying something in plant nutrition and would like to work with me via on-farm research, please let me know. I also need to share that many plant pathologists disagree with the thought of using plant nutrition: https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/publications/mythbusting-tar-spot-separating-fact-from-fiction.

For those in industry, many of you have products in trials that reduce the chelation processes and/or that help stimulate plants after being shut down (ex. from 10 days to 2-3 days) after a pesticide application. I’m curious if aiding crops out of chelation/shut down sooner helps with reducing pest/pathogen pressure? How can we better share what we observe with each other?

Tar Spot of Early Corn Update

Received several calls about tar spot yesterday and today. As of right now, it’s been confirmed by UNL at LOW incidence (1-2 lesions per leaf) in Saunders, Pierce, and Clay (on 6/16/25), Polk, and Seward Counties (on 6/17/25). I really appreciate Craig Anderson and Mike Byers bringing me leaf samples to confirm. I also appreciate those who were calling to hear of any confirmations from leaf samples.

There’s a lot of fear surrounding this disease, and still some unknowns. We haven’t seen tar spot in Nebraska this early. It would be helpful if consultants/agronomists would confirm samples to Dr. Tamra Jackson-Ziems, the UNL Plant and Pest Diagnostic Lab (tar spot testing is free), or a local Extension Educator so that we have the most accurate information to provide. Tamra will update the tar spot map at: https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/maps/tar-spot-of-corn.

We are NOT recommending fungicide application in fields where tar spot is confirmed in these early vegetative stages.

Reasons for not applying fungicide now:

1-Economics: Corn economics are already a struggle. When tar spot appeared in the early vegetative stages, research from Dr. Darcy Telenko’s lab at Purdue University showed it wasn’t economical to apply at V6-V7 as it didn’t suppress disease enough. It was economical when the corn reached tassel stage or beyond. I show the research data below and you will also see the chart on the website link I shared above. In this post, Dr. Telenko shares 7 years of experience dealing with tar spot when it occurs early in the season and how to make fungicide decisions.

*Some Quick Tips & Tools for Preparing for Tar Spot in Corn-Dr. Darcy Telenko

*Tar Spot: What to look for in corn and making an informed fungicide application-Dr. Darcy Telenko

*Crop Disease Forecasting Tool for Tar Spot

2-Applications: Dr. Tamra Jackson-Ziems shared that some products say “no more than 2 applications per year”. Using those active ingredients now would mean you could use them again around tassel but no later when you may need the fungicide to finish the season. (See Dr. Telenko’s posts above).

3-Resistance management and integrated pest management. The photo below shows the economic threshold is 5-7% leaf severity for tar spot before it’s economical to spray. We’re a long way from that threshold on leaves confirmed for tar spot thus far. Avoiding unnecessary fungicide applications and using two modes of action when fungicides are applied may help in delaying resistance.

What to do now:

1-Continue to scout fields and wait till a 5-7% threshold on leaves before applying fungicide (see photo below)

2-Observe fields as to which hybrids have more tolerance to tar spot

3-When irrigating, consider less frequent and deeper irrigations

4-Consider plant nutrition? Manganese, Zinc, Copper, Boron, Sulfur all have a role in defending plants against pathogens. Will share more thoughts in another blog post.

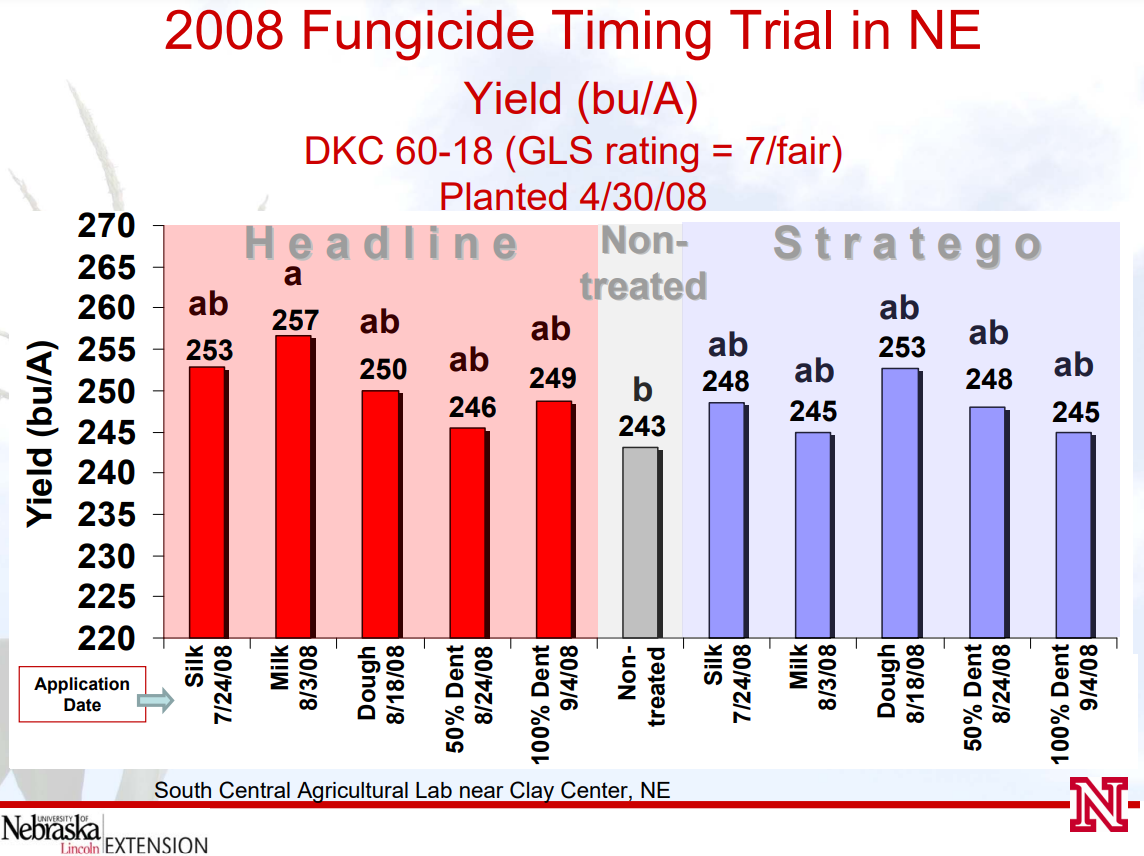

Slide courtesy of Dr. Tamra Jackson-Ziems, UNL and Dr. Telenko, Purdue University. Fungicide application at V6-V7 resulted in negative economic return and similar disease pressure as the non-treated areas. Best fungicide timing for disease suppression occurred from tassel to milk and for economic return from tassel to dough.

Differentiating Soybean Problems

Crop Update: It was great catching up briefly with so many people at Husker Harvest Days last week! We didn’t get the traditional rain anytime during husker harvest days and soybeans and non-irrigated crops turned quickly. Please slow down and watch out for slow moving vehicles as harvest has started in the area. Here’s wishing everyone a safe harvest season!

For about 10 days I was getting called to fields and answering calls about sudden death syndrome in soybeans. The majority of the situations I was called out to actually wasn’t sudden death syndrome. So, I’d like to share what to look for in order to differentiate soybean diseases. Even though soybeans are turning now, it’s helpful to know what you’re truly dealing with as you think about soybean varieties in the future.

Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS) and Brown Stem Rot (BSR) are both soil-borne fungal diseases in which the fungus is in the root and/or stem but toxins from the fungus create yellowing/brown between leaf veins on the plants. For SDS, I can usually pull those plants very easily from the soil as there’s a clear rotted taproot associated with that disease. Sometimes, you will see gray/blue fungal growth on the rotted taproot as well.

I also split the stem open, especially if the plant didn’t pull easily yet had the leaf symptoms. If the pith is brown in discoloration and is “stacked” like there’s layers of plates of tissue in it, the culprit is most likely brown stem rot. There are instances where you will have both a rotted taproot and a brown stem. In those cases, both SDS and BSR are present.

Brown pith tissue that is hollowed out and has sawdust in it is from dectes (soybean) stem borer. Dectes will not cause the leaf symptoms that SDS and BSR will. It will create a petiole with a trifoliate leaf that “flags”, meaning, it looks wilted and dying.

To be honest, the most common thing I’ve seen is the lack of a disease present. Most of the time, the taproot is in tact with a good root system, and often, there’s either whole fields or “lines” to where the symptoms are present. In those cases, I’ve suggested that this isn’t a disease issue but instead, Triazole fungicide phytotoxicity. These symptoms typically occur 2-3 weeks after a fungicide has been sprayed and either follow a spray pattern (including drift in some cases) or have field-wide distribution. Triazoles are in the Group 3 fungicide class and they move in the xylem (water-carrying vessels of the plant). Thus, their movement is dependent upon moisture. Plants that are drought-stressed lead to the fungicide product being in the tissue longer, allowing for greater injury. Other characteristics that impact the level of triazole phytotoxicity include the fungicide rate, adjuvants used, soybean genetics, and environmental conditions at the time of application. Usually leaves in the upper canopy are impacted as they were undergoing cell division (expanding) during the time of the fungicide application. For more info. please see: https://go.unl.edu/t4cg and https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/news/fungicide-phytotoxicity-on-soybean-triazole-injury-sparks-concern.

Why is this important to know? Because the next time you grow soybeans, it’d be helpful to know if you need to look for specific disease resistance in the variety selected or if one needs to consider a seed treatment for SDS. If the culprit ends up being triazole fungicide phytotoxicity, take note on the fungicide and adjuvants used and also the specific soybean variety as all those factors make a difference.

(Above photo captions): Yellow/brown chlorosis between the leaf veins in the left photo due to SDS (but very similar with BSR) (photo by Jenny Rees). Right photo shows yellow/brown chlorosis between the leaf veins due to triazole fungicide phytotoxicity which looks very similar to the leaf symptoms on SDS and BSR. (Photo via Kyle Broderick).

Photos Above: Dectes stem borer hollowed out the pith of this stem. Notice the hollowed out look and absence of “stacking” in the pith. One will also observe sawdust if dectes is present. Splitting the stem further the dectes stem borer can be found (right picture-I accidentally cut it). I don’t worry about dectes for causing yield loss; we’ve been dealing with it in Nuckolls/Thayer counties since before I started in Extension. It eats out the pith but the vascular bundles in soybean are on the outside (think of tree rings)…so they’re not causing xylem and phloem disruption (or very minimal if so). The main issue with dectes is creating lodging if a windstorm occurs prior to harvest.

Disease and Fungicides

Disease and Fungicides: Tar spot has been found in Polk and York counties at moderate incidence on leaves below the ears in the Shelby/Gresham/Benedict areas thus far. So far, all the samples and photos received have been in fields that were already sprayed. I’ve received a number of questions the past few weeks on why disease is present on fields that were sprayed with a fungicide. In the samples and questions received, I ask where the disease (mostly southern rust or tar spot) is located on the plant. If located below the ear, most likely, the product didn’t penetrate the canopy below the ear leaf. Some producers have asked for increased gallonage (3 gal/acre+) in order to better penetrate the plant canopy. In nearly every case of the questions/samples received, the diseases are below the ear leaf and not above.

If the disease is above the ear leaf in fields sprayed with a fungicide, it’s possible the spores had infected the leaves but hadn’t produced visible signs of lesions until after the fungicide was applied. Products containing triazoles (Group 3) can have some curative (killing) activity to what is already present on the leaf, but they will only work if the fungus was present a few hours to a few days before a leaf was sprayed with a fungicide. It’s also possible with very tall hybrids and lower ear placement that the coverage didn’t reach the ear leaf in some of those situations. Group 7 and 11 fungicides should provide 21-28 days of control. For fields where fungicide was automatically applied at tassel, that residual has most likely worn off or will soon. I’m not aware of any fungicide resistance issues yet in corn in Nebraska.

In corn fields that haven’t been sprayed, I’ve seen low incidence of southern rust at the ear leaf and below. At some point, it may worsen, but as many fields approach dough to dent, it’s helpful that disease didn’t explode yet. Info. about fungicide app if needed at these later development stages is below. Another observation is I tend to see more disease in fields that have been sprayed that had higher rates of nitrogen applied at one time vs. spoon-feeding over time. It’s just an observation and may not hold true, but it’s something observed thus far.

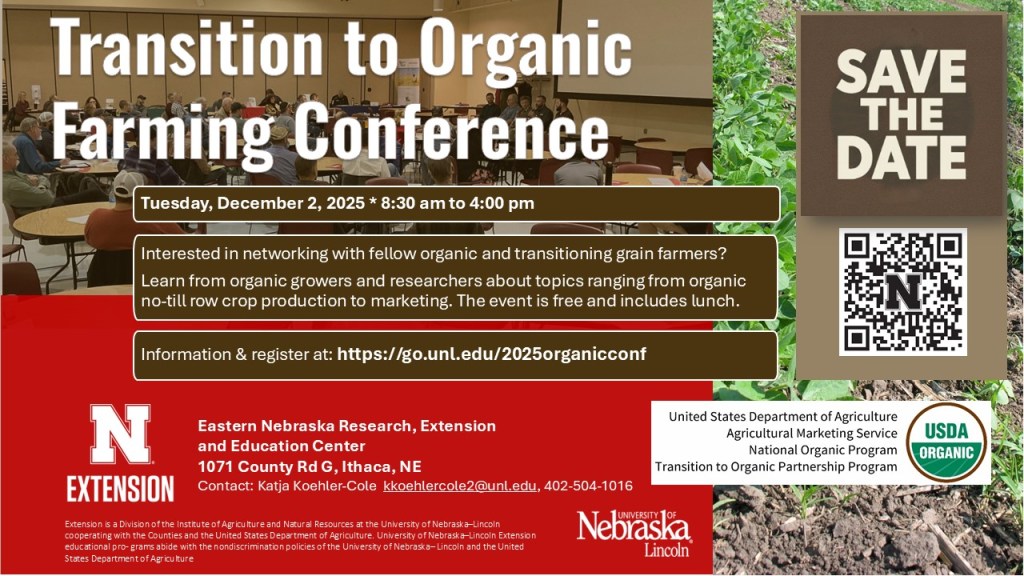

Dr. Tamra Jackson-Ziems had a fungicide timing study for two years (2008 and 2009) at South Central Ag Lab which showed fungicides could be applied through 100% dent (watch pre-harvest intervals) and had no yield difference compared to tassel in a year without southern rust pressure but heavy gray leaf spot pressure. I think we’d be more comfortable with applying no later than dough/early dent instead of 100% dent. The data is why I recommend delaying fungicide apps till needed. Several asked about the need for second fungicide apps if fields have higher disease pressure at ear leaf and below. That’s going to be a farmer/agronomist and field by field decision. The economics are tough this year with one app much less two.

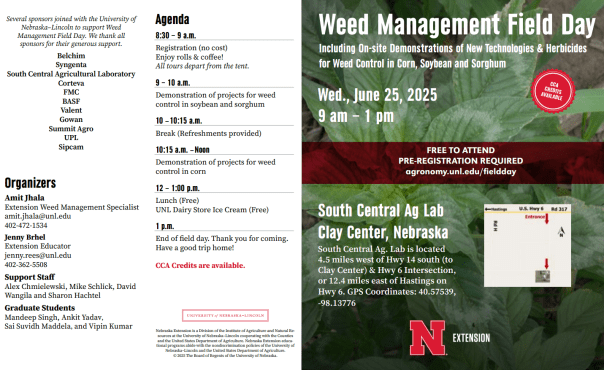

Soybean Management Field Days: Would like to encourage and remind you of the upcoming Soybean Management Field Day at Scott Richert’s farm near Ulysses on Thursday, Aug. 15 from 6-8 p.m. (Reg. at 5:30 p.m.). Google map pin of the location at https://go.unl.edu/smfd3. It’s on the Butler/Seward Co. line on Rd. 21 (Ashland Rd) between Roads D and E in Butler Co. and Roads 434 and 420 in Seward Co. I’m grateful we were able to change this program to be more relevant to the area and showcase what the farmers are doing. If you’re interested in hearing more about how small grains like rye can help with palmer and white mold control, hear about learning experiences with roller crimping, and learn about various soybean seed treatments, we hope you’ll join us! Please RSVP for meal count but walk-ins are welcome (402-624-8030 or https://enreec.unl.edu/soydays).

July 2024 Crop Update

The past 10 days, my top questions have been around fungicide recommendations, control of Japanese beetles, and hail damage. I feel there’s an increasing segment of agronomy that is focused on preventing pests based on fear. I’m grateful for those agronomists who only recommend products when warranted by scouting.

Some thoughts, although not popular, for consideration. Fungicide for white mold in soybean is pricey. If the field didn’t have a history of white mold, I wouldn’t recommend applying a fungicide for white mold. For seed corn fields without a history of white mold, I’d wait to see if white mold develops. If too fearful, would only apply one application at R2. Only fields with a history of white mold would I be considering preventive fungicide applications. And in those fields, if the beans had been planted green into a small grain and/or if a biological product with activity against white mold was used, would suggest scouting and applying only if white mold was present. Fungicide efficacy ratings: https://cropprotectionnetwork.s3.amazonaws.com/soybean-foliar-efficacy-2024.pdf.

Hail: Looked at quite a bit of hail damage in Clay/Fillmore counties last week. Always so hard to see beautiful crops impacted or destroyed. Some hail resources for you: late vegetative/tasseling in corn: https://go.unl.edu/y3of, Soybean decisions: https://go.unl.edu/z7ad; and hail damage info. on my blog at https://jenreesources.com.

Corn Diseases: There’s very little I’ve seen in fields. Bacterial leaf spot (BLS) is common on hybrids and can be confused with gray leaf spot. BLS has longer, thinner lesions with wavy lines when looking at the lesions closely. I’ve seen quite a bit of Goss’ wilt, as early as V8. There’s nothing we can do for either BLS or Goss’s as bacterial diseases, but it’s good to be aware they’re occurring.

Tar spot has been found in Richardson, Nemaha, Saunders, Dodge, Colfax counties but not in our area. Southern rust has been found in northeast Kansas. I still recommend waiting on fungicide applications until we need them. Research found that products applied between tasseling and milk when tar spot was present in low amounts (5%) was effective in controlling tar spot most years. So, waiting could be wise with tight economics, particularly if tar spot, gray leaf spot, and southern rust come in later.

Japanese Beetles in crop fields: Usually the beetles congregate in areas in the field and not whole fields. So even at a 20% defoliation in soybeans during reproductive stages, it’s been hard to pull triggers for spraying because it’s not field-wide defoliation (and we’ve seen soybeans recover in the past). For corn, the threshold is 3 beetles per ear with silks clipped less than ½” and 50% or less of the field is pollinated. A challenge with Japanese beetles is that we have another potentially 4-6 weeks of emergence from grassy areas. So, one can spray an insecticide, but it’s not uncommon to see the beetles damaging fields again once the residual wears off. Spidermites can also be flared upon insecticide applications. Some consider a border app since they begin feeding in the borders. So, those are all things to consider.

Sevin and Japanese Beetles: For homeowners, PLEASE read the pesticide labels before applying products (even if you’ve used that same product in the past). I do mention Sevin as a product that can be applied in different situations in this guide: https://go.unl.edu/xgd6, but not all Sevin formulations are the same; thus, not all the same plants are labeled! We’ve unfortunately seen some plants injured to the point of death in the past. So please, double check that the plant is labeled before applying an insecticide product to control the beetles.

For soybean damage, the situations with pictures shown here (other than the top right) will recover. These fields are already showing new growth in axillary buds including new leaves and flowers. While some canopy was lost, they will look a lot better in 7-10 days. Look for areas of the field (lower right picture) that were protected such as by trees and/or pivot tires, to determine the original development stage when the soybeans were damaged. In the case of the upper right photo, those beans were planted the week of April 10th and were already at a strong R4 to beginning R5. By R5, soybeans will not recover because all new node, leaf, and pod development ceases. If considering to replant any beans, there’s risk of using later than a 2.5 maturity variety with a July 15th planting date in reaching maturity before a frost. By July 20th, aiming for closer to a 2.0 maturity is wise. Also, if you’re replanting into soybeans, we’ve found a fungicide seed treatment is wise as phytophthora root rot tends to be a problem in replant.

For corn, much of the corn I looked at has mostly leaf stripping and will be ok. There’s also bent/broken plants. Fields vary in the amount of stem bruising. When taking stand counts, I push a little hard on plants to see if they break off when I’m taking counts. A rule of thumb we’ve used in the past: every plant in 1/1000th of an acre we give 10 bu/ac to. So, a count of 12 plants has a potential of 120 bu/ac. That may seem crazy; it depends on how things pollinate, how damaged the ears are, final stand, etc. but it has been in the ballpark in enough cases for me to still use it as a guideline for making hail damage decisions.

In these photos, the fields were far more severely damaged. There’s fields like we saw in 2023 where 1/3 of the field or less still has tassels (top left and middle photos). We saw crop insurance delay that decision in the past to see how the ears would pollinate. I’m not sure what they will decide this year. I was seeing a few brown silks in some of these field situations, but it’s super early too. There’s also a large number of dead tassels in these fields (bottom right photo) that won’t provide any pollen. Tassels remaining tend to be wrapped in the newer leaves but as you see in bottom, middle photo, the tassel is trying to shed pollen inside the trapped leaves. Ears may be misshapen and damaged due to hailstones and/or being damaged and unable to emerge from sheaths (bottom left photo).

What we learned in the past is that palmer comes in quickly once the canopy opens. One can consider warrant with drops as a layby depending on how much Group 15 had been used in the field. Most chose not to go that option. Some seeded covers like brassicas/small grain into fields not totaled (flew on or haggie). Most let the palmer grow.

In the top right photo when fields were totaled, some allowed the weeds to grow and grazed with cattle or sheep. Some seeded a summer annual cover like sorghum sudan/sudangrass/pearl millet. In 2023, several crop producers chose pearl millet so they didn’t have to worry about prussic acid poisoning for those bringing in livestock or wanting to hay. Others just waited till later in the year, shredded down the stalks and planted in a small grain like oats or rye. The “blessing” with a decision in July is it can allow for more time to make a decision compared to if we were in June and the primary option was to replant. That perhaps was the biggest lesson I learned last year in working with producers. If you have specific questions or want to talk through decisions, please give me a call.

Also, it’s important to recognize that these disaster events create loss…in this case, loss of crops, pivots, bins, not only in irrigated acres but in a lot of non-irrigated acres that had more potential than most have seen in years, much less their lifetime. It’s ok to have a range of emotions surrounding this. And, it’s common to feel stressed, numb, and not want to make a quick decision. If I’ve learned one thing in my career, it’s the fact that as people, we all just need to talk about the stress and emotions we all face at times with someone we trust. My biggest piece of advice is to talk to someone just to get outside of one’s own head. There’s so much stress in life, not to mention in ag. The most common comment I’ve heard from people the past several years was they just appreciated being able to share with someone about the stress and what they were feeling. There’s also a number of mental wellness resources on the front page of CropWatch at https://cropwatch.unl.edu.

Resources:

- Summer annual forage grasses: https://extensionpubs.unl.edu/publication/g2183/2013/pdf/view/g2183-2013.pdf

- Making soybean replant decisions-what we learned: https://go.unl.edu/z7ad

- Corn damage to late vegetative/tasseling corn: https://go.unl.edu/y3of

More information and registration at: https://www.grazemastergroup.com/events.

System’s Approach to Soybean White Mold

Grateful for seasons, for fall, and that we have such beautiful fall colors this year! For whatever reason, it just doesn’t seem like we’ve seen colors like this for a few years and several have commented about the beauty this year. May we take time to notice the beauty around us each day! Also grateful for harvest being completed or nearing completion for many! Each day is one day closer to the end!

White Mold in Soybean: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (the pathogen that causes white mold) impacts over 400 plant species from 75 families including soybean, dry bean, potato, sunflower, peas. Host weed species include: pigweeds, velvetleaf, henbit, lambsquarters, ragweeds, nightshades, mustards, sunflower. Cover crop hosts include: peas, lentils, turnips, radishes, collards, common vetch, (alfalfa and clover to a lesser extent). Just reading all that is discouraging. The fungus survives in a hard, black structure called a sclerotia that looks like mouse/rat droppings and can survive in the soil for 5 years (3 years in no-till fields). Frequent irrigation, plant wetness/fog/cool conditions at flowering (like we had in 2023), narrow rows, high plant populations, and cooler weather conditions of 46-75F allow the sclerotia to develop apothecia (look like circular tan mushrooms). Under a specific pressure, the apothecia shoot spores into the canopy where they infect the soybean plants whenever they land on senescing soybean flowers.

Flowering occurs from R1-R5 in indeterminant soybeans. Thus, why white mold is difficult to control and why we can see it develop so late into the year. The fungal infection moves from the flower into the stem, disrupting water transport. Thus, why you will often see plants that look wilted as an early symptom even before you see the signs of the white fungal growth. Wilting of plants leads to premature death impacting yields like we saw with large yield hits this past year. New sclerotia are formed within and also stick out of the plant stem and pods. They fall to the ground and the cycle continues when a susceptible host is grown.

So, what do we do about it? The following information is for fields that have a history of white mold. I’d suggest looking at this from a system’s approach. One piece is to consider varieties with disease resistance. I won’t argue that’s important. However, I’m honestly hesitant to start there as I’m unsure we have strong disease packages. And some defensive varieties give up too much yield. This is my perspective and I don’t expect people to agree. For now, I suggest finding the strongest yielding genetics first because there’s large yield variation in soybean.

From there, it becomes managing the other factors that can aid in disease. Manage weeds and avoid susceptible cover crops in the field. Crop rotation is not effective if it’s only a 2 year corn/soy rotation. While I realize they won’t work for everyone’s operation and they take more management, using small grains like cereal rye before soybeans is a tool that can help with both weed and disease suppression and doing so adds another crop to a 2 year rotation. Avoid irrigation at flowering (I realize 2023 was tough) and seek to irrigate deeper and less frequent.

There’s also tradeoffs within the system regarding row spacing for weed or disease control. Results from 18 site-years of research from Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Iowa showed:

- If planting in row spacings of 15 inches or less and in fields with a history of white mold, use a seeding rate no greater than 110,000 seeds/ac.

- If planting in fields with a history of severe white mold, widen the row spacing to 30 inches and use a seeding rate no greater than 110,000 seeds/ac. UNL research shows you don’t give up yield with final plant stands at 100,000 plants/ac.

- Fungicide applications remain an effective tool for reducing white mold levels if applied between the R1 (most effective) and R3 (less effective) growth stages. Fungicides provide 0-60% control. They’re most effective if sprayed below the canopy.

- Not all fungicide products are equally effective at controlling white mold, with Endura® remaining the most effective product if applied between the correct growth stages.

- Consider downloading the Sporecaster app for white mold to better time fungicide apps based on weather conditions (found to be 81.8% accurate).

Most biological control agents should be applied at least 3 months before flowering for fungal colonization. Biological control agents and seed treatments such as Heads Up® were shown as effective tools to reduce severity of white mold and SDS based on Iowa State research. Plant nutrition is also showing promise and that’s something I’d like to try next year with a few growers; please let me know if you’re interested. Hydrogen peroxide products had little to no success in Wisconsin research (provided only 4 hours of activity killing spores). None of the things mentioned here are exclusive, but a combination of many of these factors as a system’s approach can help in the battle against white mold.

To view tables of the fungicide research results for white mold go to: https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/publications/modern-integrated-management-practices-for-controlling-white-mold-of-soybean

JenREES 10/8/23

Soybean Cyst Nematode: 2023 was a year for soybean diseases. I’ve been thinking about the soybean disease problems we’ve had and am planning a series of columns to talk through thoughts on management. Will focus on soybean cyst nematode for this week.

After soybean harvest is a prime time to sample for soybean cyst nematode as they’ll be at their highest levels in the soil. Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) is considered the #1 soybean disease in the U.S. as it can rob yield (up to 40%) with or without the presence of symptoms on soybean plants. When symptoms are present, they can include patchy areas of fields that may contain chlorotic and/or stunted plants. Digging up plants and carefully looking around the roots, one may observe tiny white specks that look like sand grains. With closer observation, if it is SCN, the specks will appear lemon-shaped as the female soybean cyst nematode. Technically, when the female body turns brown and dies is when it is called a ‘cyst’. Each cyst protects and contains up to 400 eggs each. When soybean is planted, juvenile nematodes hatch from eggs within the cysts during the right moisture and temperature conditions. The nematodes migrate to soybean roots where they infect, feed, breed, and then females produce new cysts full of eggs. This lifecycle occurs 3-4 times during the summer, thus, SCN populations can rapidly increase in a field in one year.

I saw that this year, a handful of times. Most field situations didn’t only have SCN as the problem, but I saw SCN populations rapidly increase from the first time fields were sampled to the next time. As you or agronomists are taking soil fertility samples this fall, split part of the 0-8” (or 0-6”) sample for testing for SCN. Or, take the soil sample in areas where the yield monitor showed yields were very low, patches where you saw disease, or field entryways. It’s also wise to take a sample from a good portion of the field for comparison. In soybean fields, take the sample a few inches off the old soybean row. However, SCN samples can also be taken from corn or other crop fields to help inform decisions if rotating to soybean next year. Place the sample cores (12-20 in total) in a plastic bucket, mix, then place in your sampling bag. I use quart-sized ziplock type bags, but there’s also SCN sampling bags available at local Extension Offices or directly from the UNL Plant and Pest Diagnostic clinic (402-472-2559). Label the bag with your contact info., field name, and that you want SCN analysis. Also be sure to fill out a completed sample submission form requesting SCN analysis and mail the samples to the UNL Plant & Pest Diagnostic Clinic (1875 North 38th Street, 448 Plant Science Hall, Lincoln, NE 68583-0722). There’s no charge for the sample analysis thanks to the Nebraska Soybean Board and your checkoff dollars. Knowing if you have SCN is the first step in management. Will share more on management in future columns.

Caring for Drought-stressed trees/shrubs: With the continuing dry conditions, this is a critical time to prepare woody plants for winter and prevent winter injury, especially to evergreens. Dry fall conditions can reduce the number of leaves, blooms and fruits trees produce the next season. Trees often delay the appearance of drought-stress-sometimes months or years after the stress occurs. Drought-stressed trees are more susceptible to secondary attack by insect pests and disease problems, such as borers and canker diseases, which can cause tree death. When watering, moisten the soil around trees and shrubs, up to just beyond the dripline (outside edge of tree leaf/needle canopy), to a depth of 8 to 12”. Avoid overwatering; but continue to water until the ground freezes as long as dry conditions persist. Use a screwdriver pushed into the soil to gauge the depth of watering.

Cedar beetles (Cicada parasite beetles): Have gotten a few calls about numerous beetles on ash and other trees that were crawling on them and flying around. The ones I’ve received samples of are cedar beetles, also known as cicada parasite beetles, which were new for me to learn about. They are about one inch long, and dark brown or black. The males have short, comb-like antennae. The beetles are harmless to trees and are laying eggs in the bark cracks. Larvae hatch, travel down tree cracks and burrow through soil looking for cicada nymphs to feed on their blood. So, they’re considered a parasite of cicadas, not of trees, and no control is needed.

Cedar beetles/Cicada parasite beetles