Blog Archives

Soybean Seed Size and Yield Impacts

Soybean Seed Size and Yield: Dr. Jim Specht, Emeritus UNL Soybean Physiologist, wrote a couple articles for CropWatch (https://cropwatch.unl.edu). One contains a quick method to determine yields using seed size just prior to harvest. The other is about water stress timing. Sharing key points that applied to soybean yields in our area of the State this year when it came to weather, soy development, seed size, and yield. This doesn’t reflect disease impacts.

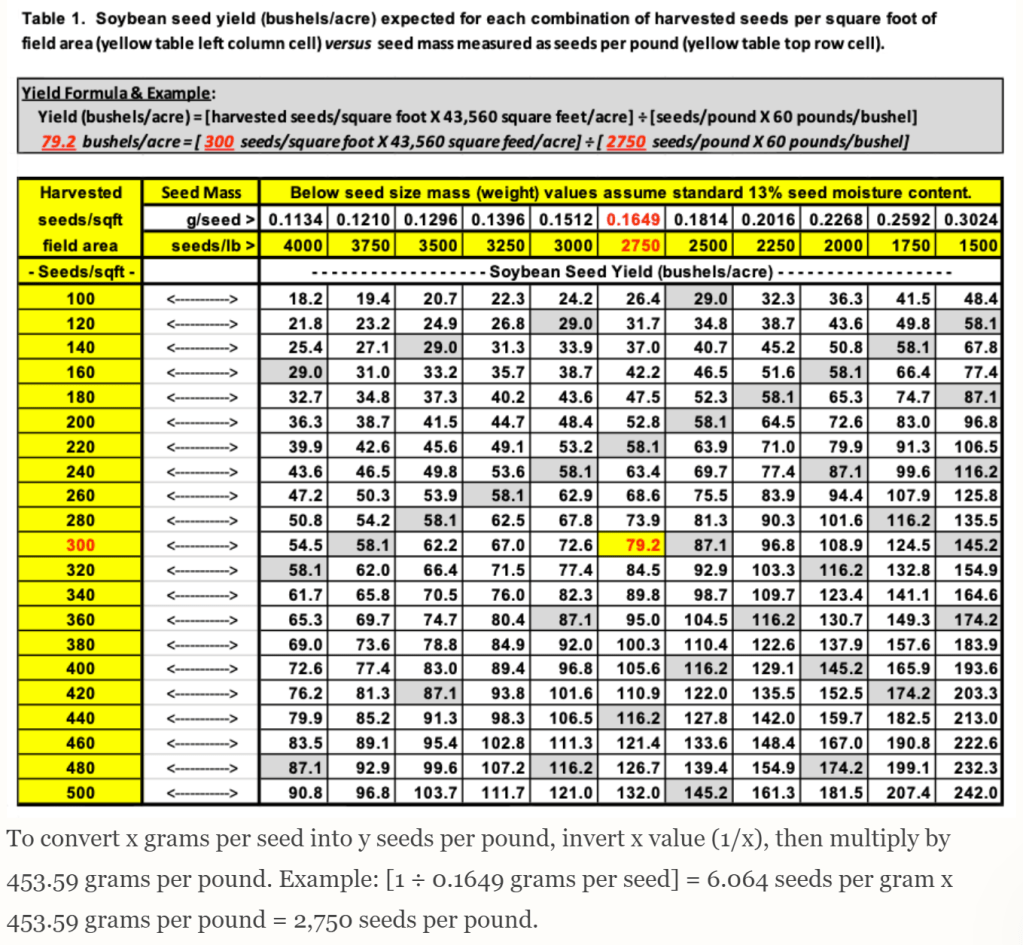

During soybean reproductive development, three stages — R1-R2 (flowering), R3-R4 (podding), and R5-R6 (seed-filling) — occur successively during July and August in the growing season. Soybean yield is ultimately a function of two components: the harvested seed number (in terms of unit land area), and the seed mass (weight of the average harvested seed). Seed number is set during the R1 to R4 stages of flowering and podding, though abortion of pods or seeds in those pods can occur in the later R stages. Seed mass (i.e., size) is set during the R5 to R6 stages of seed-filling, as the seeds undergo enlargement until the R6 stage ends at the onset of the R7 (physiological maturity) stage.

Jim and colleagues conducted a 3-year study in the 1980’s looking at the drought-stress sensitivity of seed number and seed size during different R stages. It involved 14 Group 0-Group 4 soybean varieties using seven treatments — each consisting of a single irrigation application, but each treatment differed with respect to the R stage coinciding with the single irrigation event.

When the single irrigation was applied during flowering, they saw a substantial increase in seed number, yet also a lower seed mass compared to the control rainfed treatment. This indicated that when water stress is mitigated during flowering (but not thereafter), soybean plants will set more seeds, but also end up making those seeds smaller when water is not adequate thereafter. We normally don’t recommend irrigation during flowering to avoid disease onset, but this year was a year where irrigation was necessary in many fields in this part of the State.

In contrast, when a single irrigation is applied during seed-fill (R5-R6), fewer seeds are set (and/or retained) due to prior water stress, but the mass of those fewer seeds is optimized due to the late-applied single irrigations that mitigate any coincident water stress.

They also found a response pattern coinciding with an irrigation event occurring at R3.5 and R4.5 (podding) that showed plants in that stage are conditioned to enhance seed mass while still increasing seed number to some degree. Irrigating at this stage resulted in the highest yields among treatments. Thus, why we typically encourage first irrigation of soybeans at R3 in our silt-loam soils. Additional research in the early 2000’s verified this.

However, it wasn’t reality for us to start irrigating at R3 this year. Many were irrigating since planting or as early as V2 with gravity irrigation after ridging tiny beans. The research also showed a full-season multiple irrigation treatment that resulted in maximized seed number, but seed mass was not increased beyond the increase achieved with single irrigation at R3.5. Thus, by irrigating all season (or in a season where rainfall provides no water stress), seed number (which is set before seed mass) is prioritized by stress-free plants relative to optimization. As we think about this past year, many fields may have experienced moisture stress at some point and all experienced heat and other environmental stresses.

Many soybeans that were early planted and early maturing experienced the stress of a hot and dry late June as flowers began setting which transitioned into a mostly wet/cool July during the seed number setting stages of R1-R2 (flowering) and R3-R4 (podding). The transition to a dry/hot August during the seed mass setting stages of R5-R7 (seed-filling) resulted in a reduction in the size of the harvested seeds, which means that more (small) seed will be required per pound. Thus, impacting yield. In comparison, the later maturing beans (including early planted ones), were in those flowering and podding stages longer to take advantage of the cooler conditions. They were also in the seed fill stages into mid-September during a period of cooler temperatures. Thus, I’ve heard better yield and seed size with Group 2.8-Group 3.1 beans.

While the weather is outside our control, I hope this is helpful in thinking through this past year. For risk mitigation going forward, I think it shows the importance of planting varying maturity groups to help spread risk with variations in weather conditions each year.

Prussic acid test strips: I ordered a roll of these, so if you’re grazing sorghum species, it’s a quick way to determine the presence of prussic acid, especially with light frost events. Otherwise, we recommend to pull cattle for at least 5 days post-freeze. They’re in York Ext. Office right now, so please call if you want to pick some up.

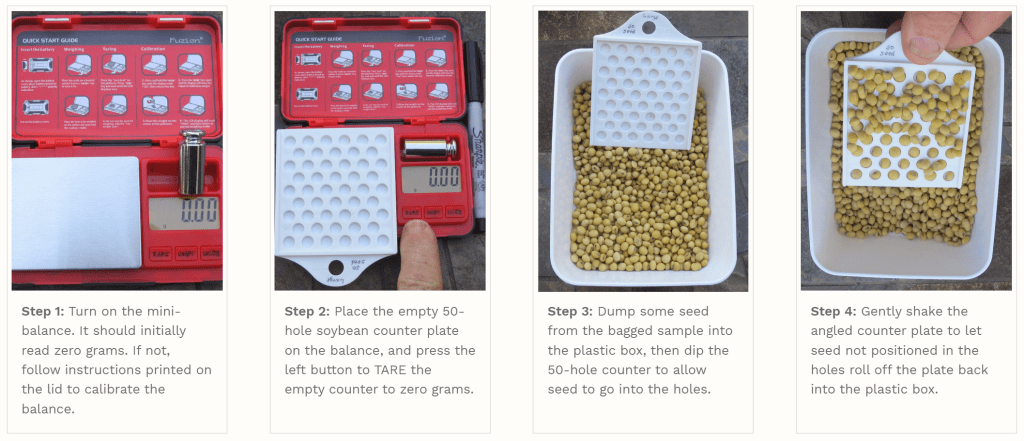

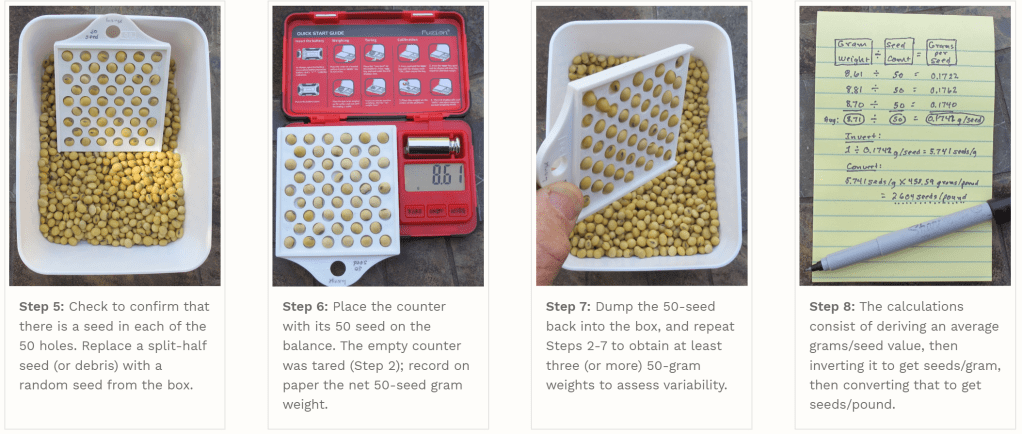

The following is how Dr. Jim Specht walks through determining soy yields just prior to harvest using seed size. These photos are via Dr. Specht.

Looking at the above chart, Alex Harrell from Georgia who reported a record soybean yield of 206.8 bushels/acre in 2023 suggested that the harvested seed in field likely had a seed mass of around 1,675 seeds/pound. Thus, a large seed size with (doing the math) around 477 seeds per square foot on a plant population of 77,000 plants/ac.

Soybean Stem Borer

Are you noticing holes in your soybean stems? Holes where the petiole meets the main stem are the entry point where soybean stem borer (also known as Dectes stem borer) larvae tunnel into the main soybean stem. Originally eggs are laid in soybean leaf petioles in the upper canopy. The eggs hatch into larvae which burrow down the petiole then into the main soybean stem. Notice the soybean stem borer infected stem in the middle while the soybean stem to the right has a a non-infested area where the petiole dropped (it is naturally sealed over by the plant). Count how many plants out of 20 have this symptom to get an idea of percent infestation and repeat in several areas of the field. Fields with 50% or more infestation need to be harvested first and perhaps earlier to avoid lodging and yield loss associated with lodging.

Lodged soybeans can be another key for checking for stem borer around harvest time. Notice the stem in the middle of the photo that is lodged (fallen over instead of standing in the row).

Following the stem to the base, the stem easily breaks away from the plant. The stem itself will appear solid. The base of the plant where it breaks is also often sealed off. The stem borer will seal itself inside the base of the stem. In this case, there’s a small portion that hasn’t been sealed off yet.

Gently pulling apart the base of the stem reveals the soybean stem borer larva. The larva will spend the winter and eventually pupate here. Adult beetles will emerge in late June and there’s only one generation per year. For more information specific to life cycle and management, please see the following NebGuide.

Harvest #Soybeans at 13%

In spite of green stems and even leaves on some plants, soybeans are surprisingly drier than what you may think. I’ve been hearing reports of  soybeans in the 7-10% moisture range already in spite of there also being some “lima beans” along with the low moisture beans at harvest.

soybeans in the 7-10% moisture range already in spite of there also being some “lima beans” along with the low moisture beans at harvest.

Harvesting soybeans at 13% moisture is a combination of skill and maybe some luck. Why is 13% so critical? A standard bushel of soybeans weighs 60 lbs. and is 13% moisture. Often beans are delivered to the buyer at lower moisture than 13%. The difference between actual and desired moisture content will result in lost revenue to the grain producer. Here’s how the loss works based on UNL Extension’s “10 Easy Ways to boost profits up to $20/acre”:

- Since 13 percent of the weight is water, only 87 percent is dry matter. The dry matter in a standard bushel is 52.2 pounds and the remaining 7.8 pounds is water.

- If this bushel of soybeans is kept in an open basket and some moisture is allowed to evaporate, the net weight of beans would decrease. If the dry matter weight remains unchanged at the standard 52.2 pounds, the wet basis weight for any moisture content can be calculated.

- For example, a standard bushel at 13 percent moisture weighs 60 pounds. If the moisture content were reduced to 11 percent (89 percent dry matter), the wet basis weight per bushel of the soybeans would be 52.2 pounds of dry matter divided by .89=58.65 pounds. (1.35 pounds less than the standard 60 lb. weight of beans initially placed in the basket). For each 52.2 pounds of dry matter delivered at 11 percent moisture, you miss an opportunity to sell 1.35 pounds of water.

- It is standard practice for buyers to assume 60 pounds of soybeans constitutes a bushel when soybeans are at or below 13 percent moisture. When the beans are below 13 percent, the difference in water content is made up for by an equal number of pounds (wet basis) of soybeans.

- Assuming a 60 bushel per acre yield and selling price of $8.50 per bushel, the potential extra profit the producer could realize if the beans are harvested at 13 percent moisture instead of 11 percent is $11.48 per acre.

Rapid dry-down and difficulty harvesting green stems and pods are the most common reasons for harvesting at lower than standard moisture. The following practices can help producers maintain quality and expected moisture content.

- Adjust harvest practices. When harvesting tough or green stems, make combine adjustments and operate at slower speeds.

- Begin harvesting at 14 percent moisture. Try harvesting when some of the leaves are still dry on the plant; the beans may be drier than you think. Soybeans are fully mature and have stopped accumulating dry matter when 95 percent of the pods are at their mature tan color.

- Plan planting dates and variety selection to spread out plant maturity and harvest.

- Avoid harvest losses from shattering. Four to five beans on the ground per square foot can add up to one bushel per acre loss. Harvest at a slow pace and make adjustments to the combine to match conditions several times a day as conditions change.